How to get your notebook server running (Quickstart)

What are Jupyter Notebooks and why would I want to use one?

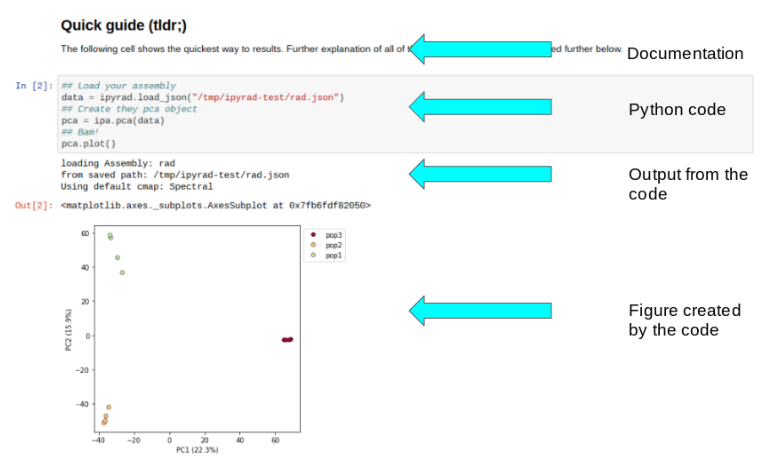

Jupyter notebooks are primarily a way to generate reproducible scientific analysis workflows in python. You can mix documentation, code, tables, and figures in one executable document which can easily be shared and published to the web. Here is a good examle of a notebook demonstrating the ipyrad.analysis.pca module. In this notebook you can see the benefit of intermingling expanatory text, with executable code, and results:

And this is not a static document! I can open this notebook and recreate my entire analysis, or even tweak things and rerun it without having to wrangle a ton of different scripts, or try to remember the parameters for a bunch of esoteric analyses I ran, or even remember which analyses I ran, because they’re all here in one document.

Insert live notebook demo

If you are familiar with RStudio, the workflow is somewhat similar, the main difference being that with jupyter notebooks you can export your entire session with figures, tables, and results, all embedded between consecutive “tasks” specified by blocks of code.

ipyrad analysis tools are best run inside Jupyter notebooks, as the analysis can be monitored and tweaked and provides a self-documenting workflow, so we will focus the rest of the workshop on exploring the anaylsis tools in the jupyter notebook environment.

A word on Jupyter notebook setup in an HPC environment

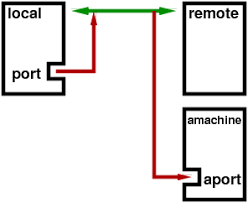

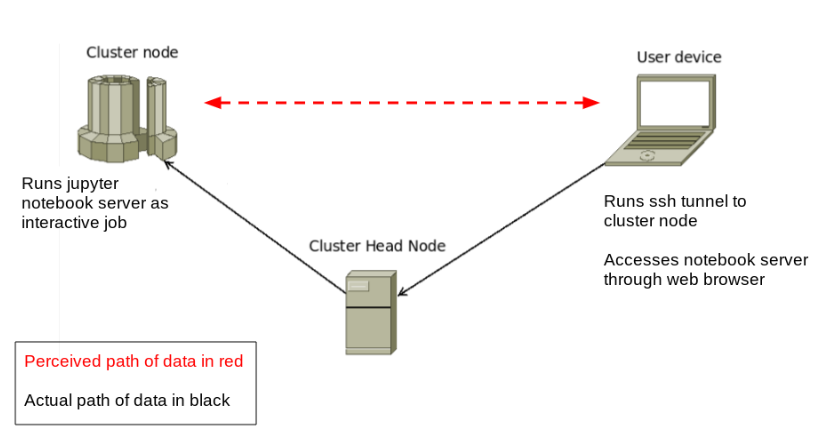

Jupyter notebooks running on a cluster require a special kind of connection called an SSH Tunnel. We need to do this because we really only can “see” the head node from the outside world. In other words, we can only ssh directly to the head node, we can not ssh directly from our laptops to the compute nodes. Yet, the compute nodes are where we want to run the notebooks, so what are we to do? Since we can ssh to the head node, and since we can do basically whatever we want once we are there, we can set up a “tunnel” to route messages from our laptop to the compute nodes. Here’s a diagram of the process, where the green arrow indicates the SSH tunnel, and the red arrows indicate the messages being passed between your laptop and the cluster, essentially using ssh to “tunnel” traffic between these two computers:

The end result is that we’ll be able to sit on our laptops and run complicated analyses on the compute node as if we were actually running directly on the cluster, in this way taking advantage of both the resources of the cluster, and the convenience of the notebook environment:

Getting Set up with Jupyter Notebooks

Setting up a jupyter notebook session involves running one command on your local machine, and a couple of commands on the cluster. Some of these commands are picky so it’s important to be careful and pay special attention until you’re very comfortable with the process.

Overview of process

- Set Jupyter notebook password

- Create the config file

- Start remote notebook server

- Establish jupyter notebook ssh tunnel: Windows - Mac/Linux

- What do do if your notebook isn’t working

- More information about jupyter

Set Jupyter Notebook Password

Jupyter was already installed as a dependency of ipyrad, so we just need to set a password before we can launch it. This command will prompt you for a new password for your notebook (you will only ever have to do this once on the HPC). Run this command in a terminal on the head node:

$ jupyter notebook password

This will set a password on your notebook server so that other people won’t have access to your files and notebooks. The notebook server will prompt you for your password when you initially connect to it.

Note: The password tho access your jupyter notebook and the password for your cluster login are two different passwords. It will probably reduce confusion, though, if you make them the same, at least for now.

Set default configuration behavior

There are a couple arguments that we always want to start the jupyter notebook with, so it is often convenient to just add these to the configuration file, rather than type them out over and over. You will only have to do this one time on the cluster.

The first parameter (open-browser = False) directs jupyter to run in

the background and wait for connections. The second parameter (port = <my_port_#>)

is very important for us. Each user must enter the port number

they were assigned on the RADCamp NYC workshop port #s page.

The final parameter (port_retries = 0)

prevents jupyter from assigning us a random port if our assigned port

is not available. This is useful because if we’re already running

a notebook server and we try to start another one we don’t want the new

one to start, rather just to be informed that we’re already running one.

We are going to use the printf command to write the 3 parameter settings

to the jupyter config file. First, just run this command and you’ll see

that printf simply prints the properly formatted parameters to the screen.

The \n character is a special character that means “put a new line here”.

$ printf "c.NotebookApp.open_browser = False\nc.NotebookApp.port = 9000\nc.NotebookApp.port_retries = 0\n"

c.NotebookApp.open_browser = False

c.NotebookApp.port = <my_port_#>

c.NotebookApp.port_retries = 0

Now we can spice it up a bit by using “output redirection”, which is a

feature of the linux command line. The > special character can

redirect output that would normally get printed to the screen and

write it to a file instead. So running the following command will

create the .jupyter/jupyter_notebook_config.py file with the

exact parameter settings we want.

$ printf "c.NotebookApp.open_browser = False\nc.NotebookApp.port = 9000\nc.NotebookApp.port_retries = 0\n" > ~/.jupyter/jupyter_notebook_config.py

Finally, use cat to convince yourself that the printf command actually

wrote the data to the config file:

cat ~/.jupyter/jupyter_notebook_config.py

Run Notebook Server on the cluster

For convenience we will run our instance of the jupyter notebook server

using a new job submission script. Begin by creating a new file in your

job-scripts directory:

$ cd job-scripts

$ nano jupyter.sh

Now enter the following text in this script. Be sure to replace your

actual port number inside the angle brackets below. All these SBATCH

flags should be familiar from yesterday:

#!/bin/sh

#SBATCH --account=edu

#SBATCH --reservation=edu_23

#SBATCH --cores=4

#SBATCH --time=8:00:00

unset XDG_RUNTIME_DIR

cd $HOME

jupyter-notebook --ip=$(hostname -i) --port=<your_port_number>

Now you can submit your jupyter server job as follows:

$ sbatch jupyter.sh

Submitted batch job 8384428

Once the job appears to be running, you must now take note of the

compute node your notebook server is running on. This can be done

using squeue. In the example results below you can see the compute

node is node162:

$ squeue -u <your_username>

JOBID PARTITION NAME USER ST TIME NODES NODELIST(REASON)

8384428 edu1 jupyter. work2 R 0:14 1 node162

Backup command: Yesterday we had some problems with the squeue command

so if you find that this isn’t running you can also try the following:

$ squeue | grep <your_username>

SSH Tunnel Configuration on your local computer

NB: In order to properly run an SSH tunnel to a notebook server on the cluster you must have both your personal port number and the name of the compute node on which the server is running.**

This part is run on your local computer. An “ssh tunnel” will allow your computer to talk to the notebook server on the cluster by using the web browser. It’s a little confusing at first, but once you see it up and running, it will make more sense and we hope you will find it very clever and useful.

Note on terms: A “port” is just a number, like the address of a house, or a telephone number. Every computer has 32,000 ports, most of which are unused. You might not know this, but when you use a web browser to look at a web page, your computer is talking to the remote server on port 80. This is standardized. When you

sshto the cluster you are making a connection on port 22, and this is standard too.

We can tell computers to talk to each other on different ports, and this is what we’ll do here, since we have 25 people who all want to talk to the cluster, we need to specify 25 different ports. Because each notebook must have a unique port number to run on, we have assigned unique port numbers for each workshop attendee. You can you can find your port number here: RADCamp NYC workshop port #s.

Special Note: An “SSH Tunnel” and an “SSH client connection” are two different things. The SSH client connection gives you access to the command line on a remote machine. The SSH tunnel will allow your web browser to talk to your jupyter notebook using ssh, but on a unique port. For a jupyter notebook to function properly you will normally always need both an ssh tunnel (for making the web interface work) and an ssh client connection (for running the jupyter notebook server).

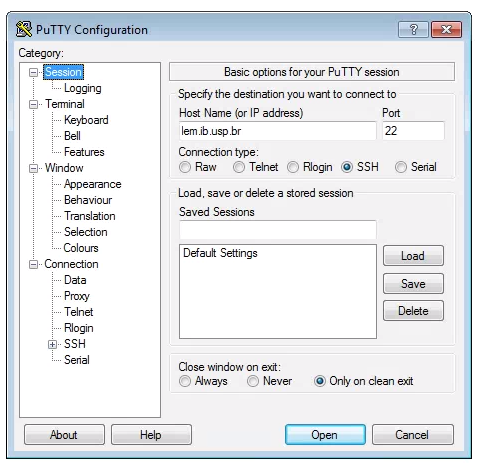

Windows SSH Tunnel Configuration

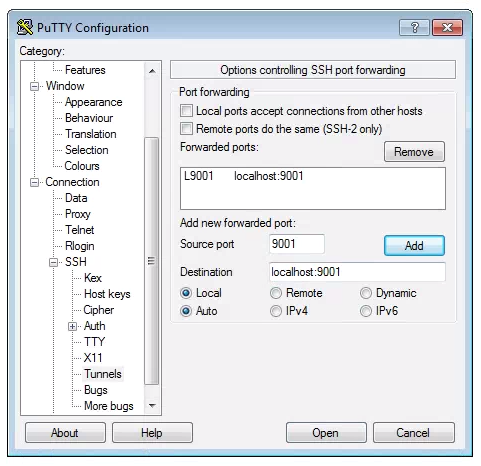

To set up a SSH Tunnel on a Windows machine, we use puTTY again. Open puTTY and fill out the host address in the first screen, like you do when connecting to the cluster.

Now, click on SSH on the left panel, and click on Tunnels. There are two boxes of interest here: Source Port and Destination. In Source Port you will put your personal port #. In Destination you should put <compute_node>:<your_port_#>. Now click “Add” and your tunnel info will appear in the empty window. Click “Open” and log in.

Mac/Linux SSH Tunnel Configuration

SSH Tunnel on Mac/Linux can be established through the command line interface. Open a Terminal and run this command:

ssh -N -f -L <my_port_#>:<compute_node>:<my_port_#> <username>@habanero.rcs.columbia.edu

This will prompt you for your password (the password on the cluster). If you type the password correctly it will look like nothing happened, but this means it worked! If you think nothing happened you should not attempt to run it again because of panic, because if you run it twice you might see this error message:

bind: Address already in use

channel_setup_fwd_listener: cannot listen to port: 9000

Note: If you see this message it means your ssh tunnel is already running!! So you should celebrate! And not panic more because you got a (seeming) error message.

Test your notebook connection (Run on your laptop)

To test your jupyter notebook configuration you can open a new browser tab and go to:

http://localhost:<my_port_#>

You should see that your notebook server prompt you for your password

before it gives you access. This is the password that you entered above

during when we used the jupyter notebook password command. If

everything is working, and you type the password correctly, then you’ll

be presented with the jupyter dashboard running on the HPC! Magic!!!

If it does not work, proceed to the section about troubleshooting jupyter notebook connections.

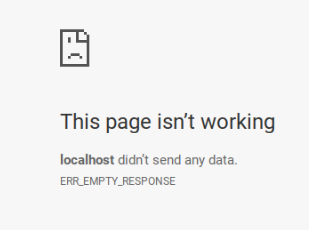

What to do if the notebook is not working

This WILL happen to everyone at least once, probably many times. You

attempt to open your web browser to http://localhost/<my_port_#> and

you see the dreaded:

1) First, DO NOT PANIC!. Randomly clicking stuff is not going to fix the problem.

2) Open a terminal connection to the cluster and make sure your notebook server is actually running.

3) On your laptop start a new ssh tunnel using the Windows or mac/linux directions.

4) In a browser open a new tab and navigate to http://localhost:<my_port_#>

5) If it still doesn’t work, ask for help.

Useful jupyter tricks/ideas

What happens if I try to run two notebook servers at the same time

If you try to run a notebook server when one is already running you’ll get a message that looks like this:

$ jupyter notebook &

<username>@darwin:~$ [I 21:06:08.325 NotebookApp] The port <my_port_#> is already in use, trying another port.

[C 21:06:08.326 NotebookApp] ERROR: the notebook server could not be started because no available port could be found.

Note: This is because of the configuration settings we have imposed in the config file, not because of an inherent limitation of jupyter. It’s common and easy to run several notebook servers on one computer.

How to tell if the ssh tunnel is running (Mac/Linux)

On your local computer open a new terminal and type:

ps -ef | grep ssh | grep habanero

If you don’t see a line that includes this ssh -N -f -L then it’s

not running, so you can restart it.

What does this error mean: “open failed: connect failed: Connection refused”?

This error indicates that your ssh tunnel is running, but your notebook server is not running. SSH to the cluster and restart your notebook server.

How to tell if the ssh tunnel is running (Windows)

I have no fuckin idea.

Killing a running jupyter notebook server

If you ever find that you have a notebook server running on the cluster and you

need to kill it, the easiest way is to use the scancel command. First you

must find the job number of the running process with the squeue command:

squeue -u work2

JOBID PARTITION NAME USER ST TIME NODES NODELIST(REASON)

8384428 edu1 jupyter. work2 R 1:48:09 1 node162

Here the JOBID is the value of interest. Now we can kill this process like so:

scancel 83484428

Starting a jupyter notebook server with command line arguments instead of a config file

You might find in the future that you want to run a jupyter notebook server

on some other computer, and that you only want to start it using command

line arguments, rather than setting up the config file. The we illustrate

usage of the three jupyter notebook arguments that correspond to the

three config file parameters we set. The first is --no-browser, which

tells jupyter to just run in the background and wait for connections.

The second is --port, which is very important for us. Each user must

enter the port number they were assigned on the RADCamp NYC workshop port #s page, and this should be the same port as entered above for the ssh tunnel. The third is --port-retries=0, which tells

jupyter to error out if our port is already occupied.

$ jupyter notebook --no-browser --port <my_port_number> --port-retries=0 &

IPython ipyparallel engines are dying? How can I solve this?

Here’s a solution. This is an esoteric problem.

echo "export QT_QPA_PLATFORM=offscreen" >> ~/.bashrc

source ~/.bashrc

Further exploration with jupyter notebooks

Here are links to a couple useful jupyter tutorials that explore much more of the functionality, should you be interested in learning more: