ipyrad command line assembly tutorial

This is the full tutorial for the command line interface (CLI) for ipyrad. In this tutorial we’ll walk through the entire assembly, from raw data to output files for downstream analysis. This is meant as a broad introduction to familiarize users with the general workflow, and some of the parameters and terminology. We will use simulated paired-end ddRAD data as an example in this tutorial, however, you can follow along with one of the other example datasets if you like and although your results will vary the procedure will be identical.

If you are new to RADseq analyses, this tutorial will provide a simple overview of how to execute ipyrad, what the data files look like, how to check that your analysis is working, and what the final output formats will be. We will also cover how to run ipyrad on a cluster and how to do so efficiently.

Each grey cell in this tutorial indicates a command line interaction.

Lines starting with $ indicate a command that should be executed

by copying and pasting the text into your terminal. Elements in code cells

surrounded by angle brackets (e.g.

## Example Code Cell.

## Create an empty file in my home directory called `watdo.txt`

$ touch ~/watdo.txt

## Print "wat" to the screen

$ echo "wat"

wat

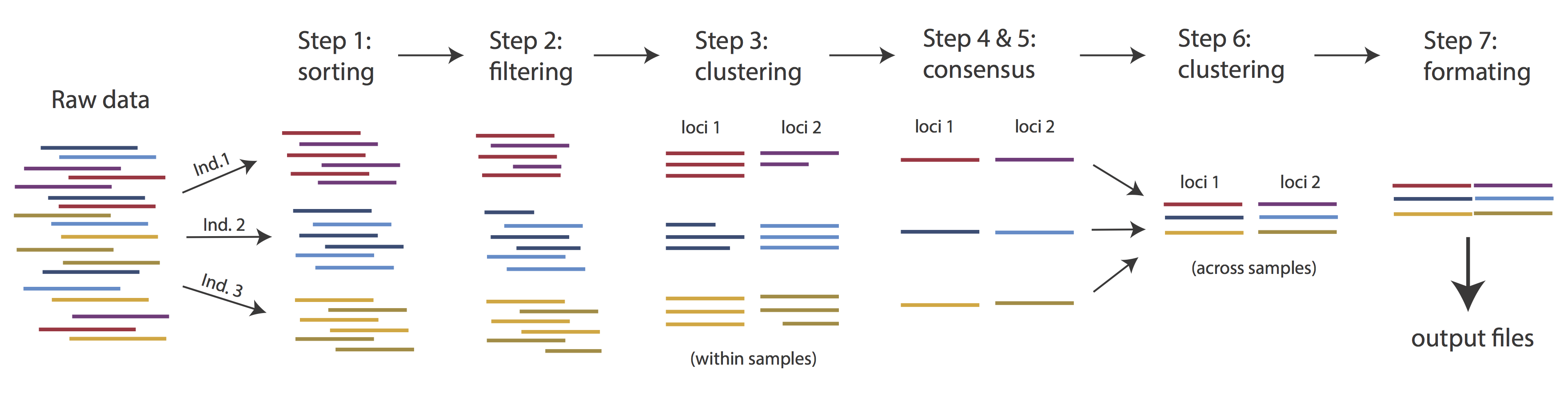

Overview of Assembly Steps

Very roughly speaking, ipyrad exists to transform raw data coming off the sequencing instrument into output files that you can use for downstream analysis.

The basic steps of this process are as follows:

- Step 1 - Demultiplex/Load Raw Data

- Step 2 - Trim and Quality Control

- Step 3 - Cluster or reference-map within Samples

- Step 4 - Calculate Error Rate and Heterozygosity

- Step 5 - Call consensus sequences/alleles

- Step 6 - Cluster across Samples

- Step 7 - Apply filters and write output formats

Note on files in the project directory: Assembling RADseq type sequence data requires a lot of different steps, and these steps generate a lot of intermediary files. ipyrad organizes these files into directories, and it prepends the name of your assembly to each directory with data that belongs to it. One result of this is that you can have multiple assemblies of the same raw data with different parameter settings and you don’t have to manage all the files yourself! (See Branching assemblies for more info). Another result is that you should not rename or move any of the directories inside your project directory, unless you know what you’re doing or you don’t mind if your assembly breaks.

Getting Started

We will be running through the assembly of simulated data using the ipyrad CLI, so if you haven’t already done so please access the CodeOcean RADCamp instance and launch a new terminal.

ipyrad help

To better understand how to use ipyrad, let’s take a look at the help argument. We will use some of the ipyrad arguments in this tutorial (for example: -n, -p, -s, -c, -r). But, the complete list of optional arguments and their explanation is below.

$ ipyrad -h

usage: ipyrad [-h] [-v] [-r] [-f] [-q] [-d] [-n NEW] [-p PARAMS] [-s STEPS] [-b [BRANCH [BRANCH ...]]]

[-m [MERGE [MERGE ...]]] [-c cores] [-t threading] [--MPI] [--ipcluster [IPCLUSTER]]

[--download [DOWNLOAD [DOWNLOAD ...]]]

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

-v, --version show program's version number and exit

-r, --results show results summary for Assembly in params.txt and exit

-f, --force force overwrite of existing data

-q, --quiet do not print to stderror or stdout.

-d, --debug print lots more info to ipyrad_log.txt.

-n NEW create new file 'params-{new}.txt' in current directory

-p PARAMS path to params file for Assembly: params-{assembly_name}.txt

-s STEPS Set of assembly steps to run, e.g., -s 123

-b [BRANCH [BRANCH ...]]

create new branch of Assembly as params-{branch}.txt, and can be used to drop samples from

Assembly.

-m [MERGE [MERGE ...]]

merge multiple Assemblies into one joint Assembly, and can be used to merge Samples into one

Sample.

-c cores number of CPU cores to use (Default=0=All)

-t threading tune threading of multi-threaded binaries (Default=2)

--MPI connect to parallel CPUs across multiple nodes

--ipcluster [IPCLUSTER]

connect to running ipcluster, enter profile name or profile='default'

--download [DOWNLOAD [DOWNLOAD ...]]

download fastq files by accession (e.g., SRP or SRR)

* Example command-line usage:

ipyrad -n data ## create new file called params-data.txt

ipyrad -p params-data.txt -s 123 ## run only steps 1-3 of assembly.

ipyrad -p params-data.txt -s 3 -f ## run step 3, overwrite existing data.

* HPC parallelization across 32 cores

ipyrad -p params-data.txt -s 3 -c 32 --MPI

* Print results summary

ipyrad -p params-data.txt -r

* Branch/Merging Assemblies

ipyrad -p params-data.txt -b newdata

ipyrad -m newdata params-1.txt params-2.txt [params-3.txt, ...]

* Subsample taxa during branching

ipyrad -p params-data.txt -b newdata taxaKeepList.txt

* Download sequence data from SRA into directory 'sra-fastqs/'

ipyrad --download SRP021469 sra-fastqs/

* Documentation: http://ipyrad.readthedocs.io

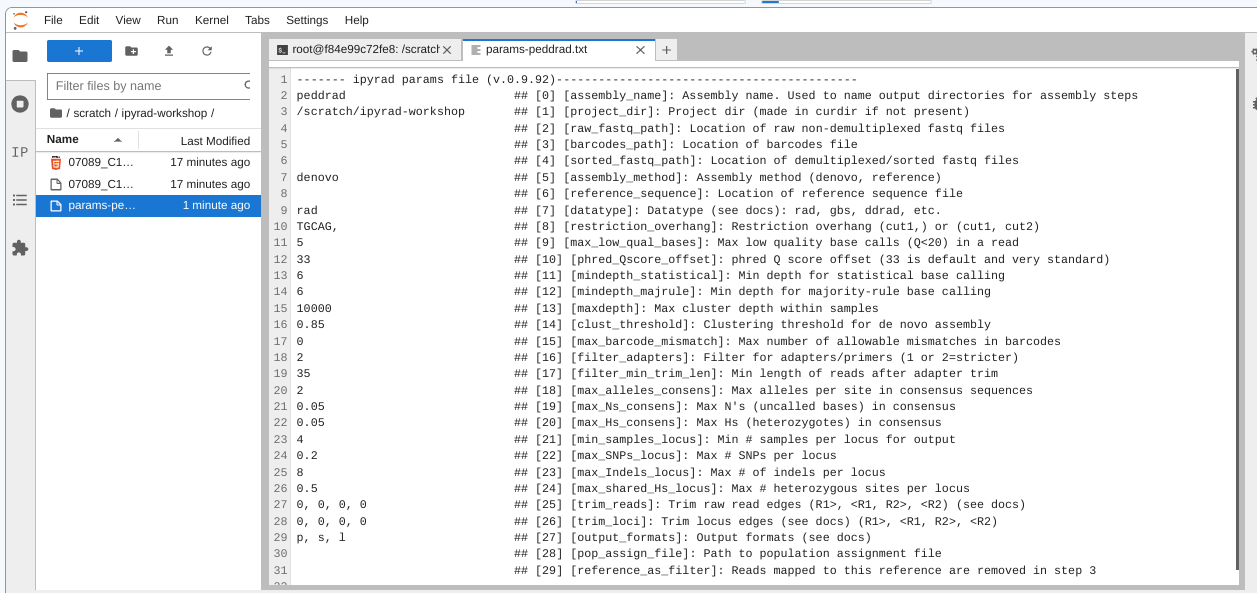

Create a new parameters file

ipyrad uses a text file to hold all the parameters for a given assembly.

Start by creating a new parameters file with the -n flag. This flag

requires you to pass in a name for your assembly. In the example we use

peddrad but the name can be anything at all. Once you start

analysing your own data you might call your parameters file something

more informative, like the name of your organism and some details on the

settings.

# First, make sure you're in your workshop directory

$ cd /scratch/ipyrad-workshop

# Unpack the simulated data which is included in the ipyrad github repo

# `tar` is a program for reading and writing archive files, somewhat like zip

# -x eXtract from an archive

# -z unZip before extracting

# -f read from the File

$ tar -xzf /ipyrad/tests/ipsimdata.tar.gz

# Take a look at what we just unpacked

$ ls ipsimdata

gbs_example_barcodes.txt pairddrad_example_R2_.fastq.gz pairgbs_wmerge_example_genome.fa

gbs_example_genome.fa pairddrad_wmerge_example_barcodes.txt pairgbs_wmerge_example_R1_.fastq.gz

gbs_example_R1_.fastq.gz pairddrad_wmerge_example_genome.fa pairgbs_wmerge_example_R2_.fastq.gz

pairddrad_example_barcodes.txt pairddrad_wmerge_example_R1_.fastq.gz rad_example_barcodes.txt

pairddrad_example_genome.fa pairddrad_wmerge_example_R2_.fastq.gz rad_example_genome.fa

pairddrad_example_genome.fa.fai pairgbs_example_barcodes.txt rad_example_genome.fa.fai

pairddrad_example_genome.fa.sma pairgbs_example_R1_.fastq.gz rad_example_genome.fa.sma

pairddrad_example_genome.fa.smi pairgbs_example_R2_.fastq.gz rad_example_genome.fa.smi

pairddrad_example_R1_.fastq.gz pairgbs_wmerge_example_barcodes.txt rad_example_R1_.fastq.gz

You can see that we provide a bunch of different example datasets, as well as

toy genomes for testing different assembly methods. For now we’ll go forward

with the pairddrad example dataset.

# Now create a new params file named 'peddrad'

$ ipyrad -n peddrad

This will create a file in the current directory called params-peddrad.txt.

The params file lists on each line one parameter followed by a ## mark,

then the name of the parameter, and then a short description of its purpose.

Lets take a look at it.

$ cat params-peddrad.txt

------- ipyrad params file (v.0.9.92)-------------------------------------------

peddrad ## [0] [assembly_name]: Assembly name. Used to name output directories for assembly steps

/scratch/ipyrad-workshop ## [1] [project_dir]: Project dir (made in curdir if not present)

## [2] [raw_fastq_path]: Location of raw non-demultiplexed fastq files

## [3] [barcodes_path]: Location of barcodes file

## [4] [sorted_fastq_path]: Location of demultiplexed/sorted fastq files

denovo ## [5] [assembly_method]: Assembly method (denovo, reference)

## [6] [reference_sequence]: Location of reference sequence file

rad ## [7] [datatype]: Datatype (see docs): rad, gbs, ddrad, etc.

TGCAG, ## [8] [restriction_overhang]: Restriction overhang (cut1,) or (cut1, cut2)

5 ## [9] [max_low_qual_bases]: Max low quality base calls (Q<20) in a read

33 ## [10] [phred_Qscore_offset]: phred Q score offset (33 is default and very standard)

6 ## [11] [mindepth_statistical]: Min depth for statistical base calling

6 ## [12] [mindepth_majrule]: Min depth for majority-rule base calling

10000 ## [13] [maxdepth]: Max cluster depth within samples

0.85 ## [14] [clust_threshold]: Clustering threshold for de novo assembly

0 ## [15] [max_barcode_mismatch]: Max number of allowable mismatches in barcodes

0 ## [16] [filter_adapters]: Filter for adapters/primers (1 or 2=stricter)

35 ## [17] [filter_min_trim_len]: Min length of reads after adapter trim

2 ## [18] [max_alleles_consens]: Max alleles per site in consensus sequences

0.05 ## [19] [max_Ns_consens]: Max N's (uncalled bases) in consensus (R1, R2)

0.05 ## [20] [max_Hs_consens]: Max Hs (heterozygotes) in consensus (R1, R2)

4 ## [21] [min_samples_locus]: Min # samples per locus for output

0.2 ## [22] [max_SNPs_locus]: Max # SNPs per locus (R1, R2)

8 ## [23] [max_Indels_locus]: Max # of indels per locus (R1, R2)

0.5 ## [24] [max_shared_Hs_locus]: Max # heterozygous sites per locus

0, 0, 0, 0 ## [25] [trim_reads]: Trim raw read edges (R1>, <R1, R2>, <R2) (see docs)

0, 0, 0, 0 ## [26] [trim_loci]: Trim locus edges (see docs) (R1>, <R1, R2>, <R2)

p, s, l ## [27] [output_formats]: Output formats (see docs)

## [28] [pop_assign_file]: Path to population assignment file

## [29] [reference_as_filter]: Reads mapped to this reference are removed in step 3

In general the defaults are sensible, and we won’t mess with them for now, but there are a few parameters we must change:

- The path to the raw data

- The barcodes file

- The dataype

- The restriction overhang sequence(s)

Open the new params file by double-clicking on params-peddrad.txt in the

left-nav file browser (you might need to navigate to this directory first).

We need to specify where the raw data files are located, the type of data we are using (.e.g., ‘gbs’, ‘rad’, ‘ddrad’, ‘pairddrad), and which enzyme cut site overhangs are expected to be present on the reads. Change the following lines in your params files to look like this:

ipsimdata/pairddrad_example_R*.fastq.gz ## [2] [raw_fastq_path]: Location of raw non-demultiplexed fastq files

ipsimdata/pairddrad_example_barcodes.txt ## [3] [barcodes_path]: Location of barcodes file

pairddrad ## [7] [datatype]: Datatype (see docs): rad, gbs, ddrad, etc.

TGCAG, CGG ## [8] [restriction_overhang]: Restriction overhang (cut1,) or (cut1, cut2)

NB: Don’t forget to choose “File->Save Text” after you are done editing!

Once we start running the analysis ipyrad will create several new directories to

hold the output of each step for this assembly. By default the new directories

are created in the project_dir directory and use the prefix specified by the

assembly_name parameter. For this example assembly all the intermediate

directories will be of the form: /scratch/ipyrad-workshop/peddrad_*.

Input data format

Before we get started with the assembly, let’s take a look at what the raw data

looks like. Remember that you can use zcat and head to do this.

## zcat: unZip and conCATenate the file to the screen

## head -n 20: Just take the first 20 lines of input

$ zcat ipsimdata/pairddrad_example_R1_.fastq.gz | head -n 20

@lane1_locus0_2G_0_0 1:N:0:

CTCCAATCCTGCAGTTTAACTGTTCAAGTTGGCAAGATCAAGTCGTCCCTAGCCCCCGCGTCCGTTTTTACCTGGTCGCGGTCCCGACCCAGCTGCCCCC

+

BBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBB

@lane1_locus0_2G_0_1 1:N:0:

CTCCAATCCTGCAGTTTAACTGTTCAAGTTGGCAAGATCAAGTCGTCCCTAGCCCCCGCGTCCGTTTTTACCTGGTCGCGGTCCCGACCCAGCTGCCCCC

+

BBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBB

@lane1_locus0_2G_0_2 1:N:0:

CTCCAATCCTGCAGTTTAACTGTTCAAGTTGGCAAGATCAAGTCGTCCCTAGCCCCCGCGTCCGTTTTTACCTGGTCGCGGTCCCGACCCAGCTGCCCCC

+

BBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBB

@lane1_locus0_2G_0_3 1:N:0:

CTCCAATCCTGCAGTTTAACTGTTCAAGTTGGCAAGATCAAGTCGTCCCTAGCCCCCGCGTCCGTTTTTACCTGGTCGCGGTCCCGACCCAGCTGCCCCC

+

BBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBB

@lane1_locus0_2G_0_4 1:N:0:

CTCCAATCCTGCAGTTTAACTGTTCAAGTTGGCAAGATCAAGTCGTCCCTAGCCCCCGCGTCCGTTTTTACCTGGTCGCGGTCCCGACCCAGCTGCCCCC

+

BBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBB

The simulated data are 100bp paired-end reads generated as ddRAD, meaning there will be two overhang sequences. In this case the ‘rare’ cutter leaves the TGCAT overhang.

- Can you find this sequence in the raw data?

- What’s going on with that other stuff at the beginning of each read?

Step 1: Demultiplexing the raw data

Since the raw data is still just a huge pile of reads, we need to split it up

and assign each read to the sample it came from. This will create a new

directory called peddrad_fastqs with two .gz files per sample, one for

R1 and one for R2.

Note on step 1: Sometimes, rather than returning the raw data, sequencing facilities will give the data pre-demultiplexed to samples. This situation only slightly modifies step 1, and does not modify further steps, so we will refer you to the full ipyrad tutorial for guidance in this case.

Now lets run step 1! For the simulated data this will take just a few moments.

Special Note: In some cases it’s useful to specify the number of cores with the

-cflag. If you do not specify the number of cores ipyrad assumes you want all of them. Our CO capsules have 16 cores so we’ll practice that here.

## -p the params file we wish to use

## -s the step to run

## -c run on 16 cores

$ ipyrad -p params-peddrad.txt -s 1 -c 16

-------------------------------------------------------------

ipyrad [v.0.9.92]

Interactive assembly and analysis of RAD-seq data

-------------------------------------------------------------

Parallel connection | d2d17ccd3643: 16 cores

Step 1: Demultiplexing fastq data to Samples

[####################] 100% 0:00:09 | sorting reads

[####################] 100% 0:00:05 | writing/compressing

Parallel connection closed.

In-depth operations of running an ipyrad step

Any time ipyrad is invoked it performs a few housekeeping operations:

- Load the assembly object - Since this is our first time running any steps we need to initialize our assembly.

- Start the parallel cluster - ipyrad uses a parallelization library called ipyparallel. Every time we start a step we fire up the parallel clients. This makes your assemblies go smokin’ fast.

- Do the work - Actually perform the work of the requested step(s) (in this case demultiplexing reads to samples).

- Save, clean up, and exit - Save the state of the assembly, and spin down the ipyparallel cluster.

As a convenience ipyrad internally tracks the state of all your steps in your

current assembly, so at any time you can ask for results by invoking the -r

flag. We also use the -p argument to tell it which params file (i.e., which

assembly) we want it to print stats for.

## -r fetches informative results from currently executed steps

$ ipyrad -p params-peddrad.txt -r

loading Assembly: peddrad

from saved path: ~/ipyrad-workshop/peddrad.json

Summary stats of Assembly peddrad

------------------------------------------------

state reads_raw

1A_0 1 19835

1B_0 1 20071

1C_0 1 19969

1D_0 1 20082

2E_0 1 20004

2F_0 1 19899

2G_0 1 19928

2H_0 1 20110

3I_0 1 20078

3J_0 1 19965

3K_0 1 19846

3L_0 1 20025

Full stats files

------------------------------------------------

step 1: ./peddrad_fastqs/s1_demultiplex_stats.txt

step 2: None

step 3: None

step 4: None

step 5: None

step 6: None

step 7: None

If you want to get even more info, ipyrad tracks all kinds of wacky stats and saves them to a file inside the directories it creates for each step. For instance, to see full stats for step 1 (the wackyness of the step 1 stats at this point isn’t very interesting, but we’ll see stats for later steps are more verbose):

$ cat peddrad_fastqs/s1_demultiplex_stats.txt

raw_file total_reads cut_found bar_matched

pairddrad_example_R1_.fastq 239812 239812 239812

pairddrad_example_R2_.fastq 239812 239812 239812

sample_name total_reads

1A_0 19835

1B_0 20071

1C_0 19969

1D_0 20082

2E_0 20004

2F_0 19899

2G_0 19928

2H_0 20110

3I_0 20078

3J_0 19965

3K_0 19846

3L_0 20025

sample_name true_bar obs_bar N_records

1A_0 CATCATCAT CATCATCAT 19835

1B_0 CCAGTGATA CCAGTGATA 20071

1C_0 TGGCCTAGT TGGCCTAGT 19969

1D_0 GGGAAAAAC GGGAAAAAC 20082

2E_0 GTGGATATC GTGGATATC 20004

2F_0 AGAGCCGAG AGAGCCGAG 19899

2G_0 CTCCAATCC CTCCAATCC 19928

2H_0 CTCACTGCA CTCACTGCA 20110

3I_0 GGCGCATAC GGCGCATAC 20078

3J_0 CCTTATGTC CCTTATGTC 19965

3K_0 ACGTGTGTG ACGTGTGTG 19846

3L_0 TTACTAACA TTACTAACA 20025

no_match _ _ 0

Step 2: Filter reads

This step filters reads based on quality scores and maximum number of uncalled bases, and can be used to detect Illumina adapters in your reads, which is sometimes a problem under a couple different library prep scenarios. We know the simulated data is unrealistically clean, so lets just pretend like there is a little noise toward the 3’ end of R1 reads. To account for this we will trim reads to 75bp.

Note: Here, we are just trimming the reads for the sake of demonstration. In reality you’d want to be more careful about choosing these values.

Edit your params file again with and change the following two parameter settings:

0, 75, 0, 0 ## [25] [trim_reads]: Trim raw read edges (R1>, <R1, R2>, <R2) (see docs)

$ ipyrad -p params-peddrad.txt -s 2 -c 16

loading Assembly: peddrad

from saved path: ~/ipyrad-workshop/peddrad.json

-------------------------------------------------------------

ipyrad [v.0.9.92]

Interactive assembly and analysis of RAD-seq data

-------------------------------------------------------------

Parallel connection | d2d17ccd3643: 16 cores

Step 2: Filtering and trimming reads

[####################] 100% 0:00:02 | processing reads

Parallel connection closed.

The filtered files are written to a new directory called peddrad_edits. Again,

you can look at the results from this step and some handy stats tracked

for this assembly.

## View the output of step 2

$ cat peddrad_edits/s2_rawedit_stats.txt

reads_raw trim_adapter_bp_read1 trim_adapter_bp_read2 trim_quality_bp_read1 trim_quality_bp_read2 reads_filtered_by_Ns reads_filtered_by_minlen reads_passed_filter

1A_0 19835 331 379 0 0 0 0 19835

1B_0 20071 347 358 0 0 0 0 20071

1C_0 19969 318 349 0 0 0 0 19969

1D_0 20082 350 400 0 0 0 0 20082

2E_0 20004 283 469 0 0 0 0 20004

2F_0 19899 306 442 0 0 0 0 19899

2G_0 19928 302 424 0 0 0 0 19928

2H_0 20110 333 462 0 0 0 0 20110

3I_0 20078 323 381 0 0 0 0 20078

3J_0 19965 310 374 0 0 0 0 19965

3K_0 19846 277 398 0 0 0 0 19846

3L_0 20025 342 366 0 0 0 0 20025

## Get current stats including # raw reads and # reads after filtering.

$ ipyrad -p params-peddrad.txt -r

You might also take a closer look at the filtered reads:

$ zcat peddrad_edits/1A_0.trimmed_R1_.fastq.gz | head -n 12

@lane1_locus0_1A_0_0 1:N:0:

TGCAGTTTAACTGTTCAAGTTGGCAAGATCAAGTCGTCCCTAGCCCCCGCGTCCGTTTTTACCTGGTCGCGGTCC

+

BBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBB

@lane1_locus0_1A_0_1 1:N:0:

TGCAGTTTAACTGTTCAAGTTGGCAAGATCAAGTCGTCCCTAGCCCCCGCGTCCGTTTTTACCTGGTCGCGGTCC

+

BBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBB

@lane1_locus0_1A_0_2 1:N:0:

TGCAGTTTAACTGTTCAAGTTGGCAAGATCAAGTCGTCCCTAGCCCCCGCGTCCGTTTTTACCTGGTCGCGGTCC

+

BBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBB

This is actually really cool, because we can already see the results of our applied parameters. All reads have been trimmed to 75bp.

Step 3: denovo clustering within-samples

For a de novo assembly, step 3 de-replicates and then clusters reads within

each sample by the set clustering threshold and then writes the clusters to new

files in a directory called peddrad_clust_0.85. Intuitively, we are trying to

identify all the reads that map to the same locus within each sample. You can

see the default value is 0.85, so our default directory is named accordingly.

This value dictates the percentage of sequence similarity that reads must

have in order to be considered reads at the same locus.

NB: The true name of this output directory will be dictated by the value you set for the

clust_thresholdparameter in the params file.

You’ll more than likely want to experiment with this value, but 0.85 is a reasonable default, balancing over-splitting of loci vs over-lumping. Don’t mess with this until you feel comfortable with the overall workflow, and also until you’ve learned about branching assemblies.

NB: What is the best clustering threshold to choose? “It depends.”

It’s also possible to incorporate information from a reference genome to improve clustering at this step, if such a resources is available for your organism (or one that is relatively closely related). We will not cover reference based assemblies in this workshop, but you can refer to the ipyrad documentation for more information.

Note on performance: Steps 3 and 6 generally take considerably longer than any of the steps, due to the resource intensive clustering and alignment phases. These can take on the order of 10-100x as long as the next longest running step. This depends heavily on the number of samples in your dataset, the number of cores, the length(s) of your reads, and the “messiness” of your data.

Now lets run step 3:

$ ipyrad -p params-peddrad.txt -s 3 -c 16

loading Assembly: peddrad

from saved path: ~/ipyrad-workshop/peddrad.json

-------------------------------------------------------------

ipyrad [v.0.9.92]

Interactive assembly and analysis of RAD-seq data

-------------------------------------------------------------

Parallel connection | d2d17ccd3643: 16 cores

Step 3: Clustering/Mapping reads within samples

[####################] 100% 0:00:11 | concatenating

[####################] 100% 0:00:02 | join merged pairs

[####################] 100% 0:00:03 | join unmerged pairs

[####################] 100% 0:00:01 | dereplicating

[####################] 100% 0:00:12 | clustering/mapping

[####################] 100% 0:00:00 | building clusters

[####################] 100% 0:00:00 | chunking clusters

[####################] 100% 0:04:00 | aligning clusters

[####################] 100% 0:00:00 | concat clusters

[####################] 100% 0:00:00 | calc cluster stats

Parallel connection closed.

In-depth operations of step 3:

- concatenating - If multiple fastq edits per sample then pile them all together

- join merged/unmerged pairs - For paired-end data merge overlapping reads per mate pair (R1/R2)

- dereplicating - Merge all identical reads

- clustering - Find reads matching by sequence similarity threshold

- building clusters - Group similar reads into clusters

- chunking clusters - Subsample cluster files to improve performance of alignment step

- aligning clusters - Align all clusters

- concat clusters - Gather chunked clusters into one full file of aligned clusters

- calc cluster stats - Just as it says.

Again we can examine the results. The stats output tells you how many clusters were found (‘clusters_total’), and the number of clusters that pass the mindepth thresholds (‘clusters_hidepth’). We’ll go into more detail about mindepth settings in some of the advanced tutorials.

$ ipyrad -p params-peddrad.txt -r

Summary stats of Assembly peddrad

------------------------------------------------

state reads_raw reads_passed_filter refseq_mapped_reads refseq_unmapped_reads clusters_total clusters_hidepth

1A_0 3 19835 19835 19835 0 1000 1000

1B_0 3 20071 20071 20071 0 1000 1000

1C_0 3 19969 19969 19969 0 1000 1000

1D_0 3 20082 20082 20082 0 1000 1000

2E_0 3 20004 20004 20004 0 1000 1000

2F_0 3 19899 19899 19899 0 1000 1000

2G_0 3 19928 19928 19928 0 1000 1000

2H_0 3 20110 20110 20110 0 1000 1000

3I_0 3 20078 20078 20078 0 1000 1000

3J_0 3 19965 19965 19965 0 1000 1000

3K_0 3 19846 19846 19846 0 1000 1000

3L_0 3 20025 20025 20025 0 1000 1000

Again, the final output of step 3 is dereplicated, clustered files for

each sample in ./peddrad_clust_0.85/. You can get a feel for what

this looks like by examining a portion of one of the files.

## Same as above, `zcat` unzips and prints to the screen and

## `head -n 18` means just show me the first 18 lines.

$ zcat zcat peddrad_clust_0.85/1A_0.clustS.gz | head -n 18

0121ac19c8acb83e5d426007a2424b65;size=18;*

TGCAGTTGGGATGGCGATGCCGTACATTGGCGCATCCAGCCTCGGTCATTGTCGGAGATCTCACCTTTCAACGGTnnnnTGAATGGTCGCGACCCCCAACCACAATCGGCTTTGCCAAGGCAAGGCTAGAGACGTGCTAAAAAAACTCGCTCCG

521031ed2eeb3fb8f93fd3e8fdf05a5f;size=1;+

TGCAGTTGGGATGGCGATGCCGTACATTGGCGCATCCAGCCTCGGTCATTGTCGGAGATCTCACCTTTCAACGGTnnnnTGAATGGTCGCGACCCCCAACCACAATCGGCTTTGCCAAGGCAAGGCTAGAGAAGTGCTAAAAAAACTCGCTCCG

//

//

014947fbb43ef09f5388bbd6451bdca0;size=12;*

TGCAGGACTGCGAATGACGGTGGCTAGTACTCGAGGAAGGGTCGCACCGCAGTAAGCTAATCTGACCCTCTGGAGnnnnACCAGTGGTGGGTAAACACCTCCGATTAAGTATAACGCTACGTGAAGCTAAACGGCACCTATCACATAGACCCCG

072588460dac78e9da44b08f53680da7;size=8;+

TGCAGGTCTGCGAATGACGGTGGCTAGTACTCGAGGAAGGGTCGCACCGCAGTAAGCTAATCTGACCCTCTGGAGnnnnACCAGTGGTGGGTAAACACCTCCGATTAAGTATAACGCTACGTGAAGCTAAACGGCACCTATCACATAGACCCCG

fce2e729af9ea5468bafbef742761a4b;size=1;+

TGCAGGACTGCGAATGACGGTGGCTAGTACTCGAGGAAGGGTCGCACCGCAGCAAGCTAATCTGACCCTCTGGAGnnnnACCAGTGGTGGGTAAACACCTCCGATTAAGTATAACGCTACGTGAAGCTAAACGGCACCTATCACATAGACCCCG

24d23e93688f17ab0252fe21f21ce3a7;size=1;+

TGCAGGTCTGCGAATGACGGTGGCTAGTACTCGAGGAAGGGTCGCACCGCAGAAAGCTAATCTGACCCTCTGGAGnnnnACCAGTGGTGGGTAAACACCTCCGATTAAGTATAACGCTACGTGAAGCTAAACGGCACCTATCACATAGACCCCG

ef2c0a897eb5976c40f042a9c3f3a8ba;size=1;+

TGCAGGTCTGCGAATGACGGTGGCTAGTACTCGAGGAAGGGTCGCACCGCAGTAAGCTAATCTGACCCTCTGGAGnnnnACCAGTGGTGGGTAAACACCTCCGATTAAGTATAACGCTACGTGAAGCTAAACGGCACCTATCACATCGACCCCG

//

//

Reads that are sufficiently similar (based on the above sequence similarity threshold) are grouped together in clusters separated by “//”. The first cluster above is probably homozygous with some sequencing error. The second cluster is probably heterozygous with some sequencing error. We don’t want to go through and ‘decide’ by ourselves for each cluster, so thankfully, untangling this mess is what steps 4 & 5 are all about.

Step 4: Joint estimation of heterozygosity and error rate

In Step 3 reads that are sufficiently similar (based on the specified sequence

similarity threshold) are grouped together in clusters separated by “//”. We

examined the head of one of the sample cluster files at the end of the last

exercise, but here we’ve cherry picked a couple clusters with more pronounced

features.

Here’s a nice homozygous cluster, with probably one read with sequencing error:

0082e23d9badff5470eeb45ac0fdd2bd;size=5;*

TGCATGTAGTGAAGTCCGCTGTGTACTTGCGAGAGAATGAGTAGTCCTTCATGCA

a2c441646bb25089cd933119f13fb687;size=1;+

TGCATGTAGTGAAGTCCGCTGTGTACTTGCGAGAGAATGAGCAGTCCTTCATGCA

Here’s a probable heterozygote, or perhaps repetitive element – a little bit messier (note the indels):

0091f3b72bfc97c4705b4485c2208bdb;size=3;*

TGCATACAC----GCACACA----GTAGTAGTACTACTTTTTGTTAACTGCAGCATGCA

9c57902b4d8e22d0cda3b93f1b361e78;size=3;-

TGCATACAC----ACACACAACCAGTAGTAGTATTACTTTTTGTTAACTGCAGCATGCA

d48b3c7b5a0f1840f54f6c7808ca726e;size=1;+

TGCATACAC----ACAAACAACCAGTTGTAGTACTACTTTTTGTTAACTGCAGCATGAA

fac0c64aeb8afaa5dfecd5254b81b3c0;size=1;+

TGCATACAC----GCACACAACCAGTAGTAGTACTACTTTTTGTTAACTGCAGCATGTA

f31cbca6df64e7b9cb4142f57e607a88;size=1;-

TGCATGCACACACGCACGCAACCAGTAGTTGTACTACTTTTTGTTAACTGCAGCATGCA

935063406d92c8c995d313b3b22c6484;size=1;-

TGCATGCATACACGCCCACAACCAGTAGTAGTACAACTTTATGTTAACTGCAGCATGCA

d25fcc78f14544bcb42629ed2403ce74;size=1;+

TGCATACAC----GCACACAACCAGTAGTAGTACTACTTTTTGTTAATTGCAGCATGCA

Here’s a nasty one!

008a116c7a22d6af3541f87b36a8d895;size=3;*

TGCATTCCTATGGGAATCATGAAGGGGCTTCTCTCTCCCTCA-TTTTTAAAGCGACCCTTTCCAAACTTGGTACAT----

a7bde31f2034d2e544400c62b1d3cbd5;size=2;+

TGCATTCCTATGGGAAACATGAAGGGACTTCTCTCTCCCTCG-TTTTTAAAGTGACTCTGTCCAAACTTGGTACAT----

107e1390e1ac8564619a278fdae3f009;size=2;+

TGCATTCCTATGGGAAACATGAAGGGGGTTCTCTCTCCCTCG-ATTTTAAAGCGACCCTGTCCAAACTTGGTACAT----

8f870175fb30eed3027b7aec436e93e6;size=2;+

TGCATTCCTATGGGAATCATGGAAGGGCTTCTCTCTCCCTCA-TTTTTAAAGCAACCCTGACCAAAGTTGGTACAT----

445157bc1e7540734bf963eb8629d827;size=2;+

TGCATTCCTACGGGAATCATGGAGGGGCTTCTCTCTCCCTCG-TTTTTAAAGCGACCCTGACCAAACTTGGTACAT----

9ddd2d8b6fb52157f17648682d09afda;size=1;+

TGCATTCCTATGAGAAACATGATGGGGCTTCTCTTTCCCTCATTTTTT--AGTTAGCCTTACCAAAGTTGGTACATT---

fc86d48758313be18587d6f185e5c943;size=1;+

TGCATTCCTGTGGGAAACATGAAGGGGCTTCTCTCTCCATCA-TTTTTAAAGCGACCCTGATCAAATTTGGTACAT----

243a5acbee6cd9cd223252a8bb65667e;size=1;+

TGCATTCCTATGGGAAACATGAAAGGGTTTCTCTCTCCCTCG-TTTTAAAAGCGACCCTGTCCAAACATGGTACAT----

55e50e131ec21fce8021f22de49bb7be;size=1;+

TGCATTCCAATGGGAAACATGAAAGGGCTTCTCTCTCCCTCG-TTTTTAAAGCGACCCTGTCCAAACTTGGTACAT----

For this final cluster it’s really hard to call by eye, that’s why we make the computer do it!

In this step we jointly estimate sequencing error rate and heterozygosity to help us figure out which reads are “real” and which include sequencing error. We need to know which reads are “real” because in diploid organisms there are a maximum of 2 alleles at any given locus. If we look at the raw data and there are 5 or ten different “alleles”, and 2 of them are very high frequency, and the rest are singletons then this gives us evidence that the 2 high frequency alleles are good reads and the rest are probably junk. This step is pretty straightforward, and pretty fast. Run it like this:

$ ipyrad -p params-peddrad.txt -s 4 -c 16

loading Assembly: peddrad

from saved path: ~/ipyrad-workshop/peddrad.json

-------------------------------------------------------------

ipyrad [v.0.9.92]

Interactive assembly and analysis of RAD-seq data

-------------------------------------------------------------

Parallel connection | d2d17ccd3643: 16 cores

Step 4: Joint estimation of error rate and heterozygosity

[####################] 100% 0:00:12 | inferring [H, E]

Parallel connection closed.

In terms of results, there isn’t as much to look at as in previous steps, though

you can invoke the -r flag to see the estimated heterozygosity and error rate

per sample.

$ ipyrad -p params-peddrad.txt -r

Summary stats of Assembly peddrad

------------------------------------------------

state reads_raw reads_passed_filter refseq_mapped_reads ... clusters_hidepth hetero_est error_est reads_consens

1A_0 4 19835 19835 19835 ... 1000 0.001842 0.000773 1000

1B_0 4 20071 20071 20071 ... 1000 0.001861 0.000751 1000

1C_0 4 19969 19969 19969 ... 1000 0.002045 0.000761 1000

1D_0 4 20082 20082 20082 ... 1000 0.001813 0.000725 1000

2E_0 4 20004 20004 20004 ... 1000 0.002006 0.000767 1000

2F_0 4 19899 19899 19899 ... 1000 0.002045 0.000761 1000

2G_0 4 19928 19928 19928 ... 1000 0.001858 0.000765 1000

2H_0 4 20110 20110 20110 ... 1000 0.002129 0.000730 1000

3I_0 4 20078 20078 20078 ... 1000 0.001961 0.000749 1000

3J_0 4 19965 19965 19965 ... 1000 0.001950 0.000748 1000

3K_0 4 19846 19846 19846 ... 1000 0.001959 0.000768 1000

3L_0 4 20025 20025 20025 ... 1000 0.001956 0.000753 1000

Illumina error rates are on the order of 0.1% per base, so your error rates will ideally be in this neighborhood. Also, under normal conditions error rate will be much, much lower than heterozygosity (on the order of 10x lower). If the error rate is »0.1% then you might be using too permissive a clustering threshold. Just a thought.

Step 5: Consensus base calls

Step 5 uses the inferred error rate and heterozygosity per sample to call the consensus of sequences within each cluster. Here we are identifying what we believe to be the real haplotypes at each locus within each sample.

$ ipyrad -p params-peddrad.txt -s 5 -c 16

loading Assembly: peddrad

from saved path: ~/ipyrad-workshop/peddrad.json

-------------------------------------------------------------

ipyrad [v.0.9.92]

Interactive assembly and analysis of RAD-seq data

-------------------------------------------------------------

Parallel connection | d2d17ccd3643: 16 cores

Step 5: Consensus base/allele calling

Mean error [0.00075 sd=0.00001]

Mean hetero [0.00195 sd=0.00010]

[####################] 100% 0:00:01 | calculating depths

[####################] 100% 0:00:00 | chunking clusters

[####################] 100% 0:01:03 | consens calling

[####################] 100% 0:00:03 | indexing alleles

Parallel connection closed.

In-depth operations of step 5:

- calculating depths - A simple refinement of the H/E estimates

- chunking clusters - Again, breaking big files into smaller chunks to aid parallelization

- consensus calling - Actually perform the consensus sequence calling

- indexing alleles - Cleaning up and re-joining chunked data

$ ipyrad -p params-peddrad.txt -r

loading Assembly: peddrad

from saved path: ~/ipyrad-workshop/peddrad.json

Summary stats of Assembly peddrad

------------------------------------------------

state reads_raw reads_passed_filter refseq_mapped_reads ... clusters_hidepth hetero_est error_est reads_consens

1A_0 5 19835 19835 19835 ... 1000 0.001842 0.000773 1000

1B_0 5 20071 20071 20071 ... 1000 0.001861 0.000751 1000

1C_0 5 19969 19969 19969 ... 1000 0.002045 0.000761 1000

1D_0 5 20082 20082 20082 ... 1000 0.001813 0.000725 1000

2E_0 5 20004 20004 20004 ... 1000 0.002006 0.000767 1000

2F_0 5 19899 19899 19899 ... 1000 0.002045 0.000761 1000

2G_0 5 19928 19928 19928 ... 1000 0.001858 0.000765 1000

2H_0 5 20110 20110 20110 ... 1000 0.002129 0.000730 1000

3I_0 5 20078 20078 20078 ... 1000 0.001961 0.000749 1000

3J_0 5 19965 19965 19965 ... 1000 0.001950 0.000748 1000

3K_0 5 19846 19846 19846 ... 1000 0.001959 0.000768 1000

3L_0 5 20025 20025 20025 ... 1000 0.001956 0.000753 1000

And here the important information is the number of reads_consens. This is

the number of retained reads within each sample that we’ll send on to the next

step. Retained reads must pass filters on read depth tolerance (both

mindepth_majrule and maxdepth), maximum number of uncalled bases

(max_Ns_consens) and maximum number of heterozygous sites (max_Hs_consens)

per consensus sequence. This number will almost always be lower than

clusters_hidepth.

Step 6: Cluster across samples

Step 6 clusters consensus sequences across samples. Now that we have good estimates for haplotypes within samples we can try to identify similar sequences at each locus among samples. We use the same clustering threshold as step 3 to identify sequences among samples that are probably sampled from the same locus, based on sequence similarity.

Note on performance of each step: Again, step 6 can take some time for large empirical datasets, but it’s normally faster than step 3.

$ ipyrad -p params-peddrad.txt -s 6 -c 16

loading Assembly: peddrad

from saved path: ~/ipyrad-workshop/peddrad.json

-------------------------------------------------------------

ipyrad [v.0.9.92]

Interactive assembly and analysis of RAD-seq data

-------------------------------------------------------------

Parallel connection | d2d17ccd3643: 16 cores

Step 6: Clustering/Mapping across samples

[####################] 100% 0:00:01 | concatenating inputs

[####################] 100% 0:00:04 | clustering across

[####################] 100% 0:00:00 | building clusters

[####################] 100% 0:00:35 | aligning clusters

Parallel connection closed.

In-depth operations of step 6:

- concatenating inputs - Gathering all consensus files and preprocessing to improve performance.

- clustering across - Cluster by similarity threshold across samples

- building clusters - Group similar reads into clusters

- aligning clusters - Align within each cluster

Since in general the stats for results of each step are sample based, the output

of -r will only display what we had seen after step 5, so this is not that

informative.

It might be more enlightening to consider the output of step 6 by examining the file that contains the reads clustered across samples:

$ cat peddrad_across/peddrad_clust_database.fa | head -n 27

#1A_0,@1B_0,@1C_0,@1D_0,@2E_0,@2F_0,@2G_0,@2H_0,@3I_0,@3J_0,@3K_0,@3L_0

>1A_0_11

TGCAGGCGTAGTAAGCTTGGATGGGAGCGACCACCCGAACGAGATATCATTCACAACGTTATACATACACTGCGCnnnnCCATTATATGGTGTGATATACGTATCCTCAAACCGAATTACAAAACGATGTGCTTACGGCGTAATCTTGGTCCCG

>1B_0_16

TGCAGGCGTAGTAAGCTTGGATGGGAGCGACCACCCGAACGAGATATCATTCACAACGTTATACATACACTGCGCnnnnCCATTATATGGTGTGATATACGTATCCTCAAACCGAATTACAAAACGATGTGCTTACGGCGTAATCTTGGTCCCG

>1C_0_678

TGCAGGCGTAGTAAGCTTGCATGGGAGCGACCACCCGAACGAGATATCAATCACAACGTTATACATACACTGCGCnnnnCCATTATATGGTGTGATATACGWATCCTCAAACCGAATTACAAAACGATGTGCTTACGGCGTAATCTTGGTCCCG

>1D_0_509

TGCAGGCGTAGTAAGCTTGCATGGGAGCGACCACCCGAACGAGATATCATTCACAACGTTATACATACACTGCGCnnnnCCATTATATGGTGTGATATACGTATCCTCAAACCGAATTACAAAACGATGTGCTTACGGCGTAATCTTGGTCCCG

>2E_0_859

TGCAGGCGTAGTAAGCTTGCATGGGAGCGACCWCCCGAACGAGATATCATTCACAACGTTATACATACACTGCGCnnnnCCATTATATGGTGTGATATACGTATCCTCAAACCGAATTACAAAACGATGTGCTTACGGCGTAATCTTGGTCCCG

>2F_0_533

TGCAGGCGTAGTAAGCTTGCATGGGAGCGACCACCCGAACGAGATATCATTCACAACGTTATACATACACTGCGCnnnnCCATTATATGGTGTGATATACGTATCCTCAAACCGAATTACAAAACGATGTGCTTACGGCGTAATCTTGGTCCCG

>2G_0_984

TGCAGGCGTAGTAAGCTTGCATGGGAGCGACCACCCGAACGAGATATCATTCACAACGTTATACATACACTGCGCnnnnCCATTATATGGTGTGATATACGTATCCTCAAACCGAATTACAAAACGATGTGCTTACGGCGTAATCTTGGTCCCG

>2H_0_529

TGCAGGCGTAGTAAGCTTGCATGGGAGCGACCACCCGAACGAGATATCATTCACAACGTTATACATACACTGCGCnnnnCCATTATATGGTGTGATATACGTATCCTCAAACCGAATTACAAAACGATGTGCTTACGGCGTAATCTTGGTCCCG

>3I_0_286

TGCAGGCGTAGTAAGCTTGCATGCGAGCGACCACCCGAACGAGATATCATTCACAACGTTATACATACACTGCGCnnnnCCATTATATGGTGTTATATACGTATCCTCAAACCGAATTACAAAACGATGTGCTTACGGCGTAATCTTGGTCCCG

>3J_0_255

TGCAGGCGTAGTAAGCTTGCATGCGAGCGACCACCCGAACGAGATATCATTCACAACGTTATACATACACTGCGCnnnnCCATTATATGGTGTTATATACGTATCCTCAAACCGAATTACAAAACGATGTGCTTACGGCGTAATCTTGGTCCCG

>3K_0_264

TGCAGGCGTAGTAAGCTTGCATGCGAGCGACCACCCGAACGAGATATCATTCACAACGTTATACATACACTGCGCnnnnCCATTATATGGTGTTATATACGTATCCTCAAACCGAATTACAAAACGATGTGCTTACGGCGTAATCTTGGTCCCG

>3L_0_865

TGCAGGCGTAGTAAGCTTGCATGCGAGCGACCACCCGAACGAGATATCATTCACAACGTTATACATACACTGCGCnnnnCCATTATATGGTGTTATAYACGTATCCTCAAACCGAATTACAAAACGATGTGCTTACGGCGTAATCTTGGTCCCG

//

//

Again, the simulated data are a little boring. Here’s something you might see more typically with real data:

punc_IBSPCRIB0361_10

TdGCATGCAACTGGAGTGAGGTGGTTTGCATTGATTGCTGTATATTCAATGCAAGCAACAGGAATGAAGTGGATTTCTTTGGTCACTATATACTCAATGCA

punc_IBSPCRIB0361_1647

TGCATGCAACAGGAGTGANGTGrATTTCTTTGRTCACTGTAyANTCAATGYA

//

//

punc_IBSPCRIB0361_100

TGCATCTCAACGTGGTCTCGTCACATTTCAAGGCGCACATCAGAATGCAGTACAATAATCCCTCCCCAAATGCA

punc_MUFAL9635_687

TGCATCTCAACATGGTCTCGTCACATTTCAAGGCGCACATCAGAATGCAGTACAATAATCCCTCCCCAAATGCA

punc_ICST764_3619

TGCATCTCAACGTGGTCTCGTCACATTTCAAGGCGCACATCAGAATGCAGTACAATAATCCCTCCCCAAATGCA

punc_JFT773_4219

TGCATCTCAACGTGGTCTCGTCACATTTCAAGGCGCACATCAGAATGCAGTACAATAATCCCTCCCCAAATGCA

punc_MTR05978_111

TGCATCTCAACGTGGTCTCGTCACATTTCAAGGCGCACATCAGAATGCAGTACAATAATCCCTCCCCAAATGCA

punc_MTR17744_1884

TGCATCTCAACGTGGTCTCGTCACATTTCAAGGCGCACATCAGAATGCA-------------------------

punc_MTR34414_3503

TGCATCTCAACGTGGTCTCGTCACATTTCAAGGCGCACATCAGAATGCAGTACAATAATCCCTCCCCAAATGCA

//

//

punc_IBSPCRIB0361_1003

TGCATAATGGACTTTATGGACTCCATGCCGTCGTTGCACGTACCGTAATTGTGAAATGCAAGATCGGGAGCGGTT

punc_MTRX1478_1014

TGCATAATGGACTTTATGGACTCCATGCCGTCGTTGCACGTACCGTAATTGTGAAATGCA---------------

//

//

The final output of step 6 is a file in peddrad_across called

peddrad_clust_database.fa. This file contains all aligned reads across all

samples. Executing the above command you’ll see all the reads that align at

each locus. You’ll see the sample name of each read followed by the sequence of

the read at that locus for that sample. If you wish to examine more loci you

can increase the number of lines you want to view by increasing the value you

pass to head in the above command (e.g. ... | head -n 300).

Step 7: Filter and write output files

The final step is to filter the data and write output files in many convenient file formats. First, we apply filters for maximum number of indels per locus, max heterozygosity per locus, max number of snps per locus, and minimum number of samples per locus. All these filters are configurable in the params file. You are encouraged to explore different settings, but the defaults are quite good and quite conservative.

To run step 7:

$ ipyrad -p params-peddrad.txt -s 7 -c 16

loading Assembly: peddrad

from saved path: ~/ipyrad-workshop/peddrad.json

-------------------------------------------------------------

ipyrad [v.0.9.92]

Interactive assembly and analysis of RAD-seq data

-------------------------------------------------------------

Parallel connection | d2d17ccd3643:: 16 cores

Step 7: Filtering and formatting output files

[####################] 100% 0:00:07 | applying filters

[####################] 100% 0:00:02 | building arrays

[####################] 100% 0:00:01 | writing conversions

Parallel connection closed.

In-depth operations of step 7:

- applying filters - Apply filters for max # indels, SNPs, & shared hets, and minimum # of samples per locus

- building arrays - Construct the final output data in hdf5 format

- writing conversions - Write out all designated output formats

Step 7 generates output files in the peddrad_outfiles directory. All the

output formats specified by the output_formats parameter will be generated

here. Let’s see what’s created by default:

$ ls peddrad_outfiles/

peddrad.loci peddrad.phy peddrad.seqs.hdf5 peddrad.snps peddrad.snps.hdf5 peddrad.snpsmap peddrad_stats.txt

ipyrad always creates the peddrad.loci file, as this is our internal format,

as well as the peddrad_stats.txt file, which reports final statistics for the

assembly (more below). The other files created fall in to 2 categories: files

that contain the full sequence (i.e. the peddrad.phy and peddrad.seqs.hdf5

files) and files that contain only variable sites (i.e. the peddrad.snps and

peddrad.snps.hdf5 files). The peddrad.snpsmap is a file which maps SNPs to

loci, which is used downstream in the analysis toolkit for sampling unlinked

SNPs.

The most informative, human-readable file here is peddrad_stats.txt which

gives extensive and detailed stats about the final assembly. A quick overview

of the different sections of this file:

$ cat peddrad_outfiles/peddrad_stats.txt

## The number of loci caught by each filter.

## ipyrad API location: [assembly].stats_dfs.s7_filters

total_filters applied_order retained_loci

total_prefiltered_loci 0 0 1000

filtered_by_rm_duplicates 0 0 1000

filtered_by_max_indels 0 0 1000

filtered_by_max_SNPs 0 0 1000

filtered_by_max_shared_het 0 0 1000

filtered_by_min_sample 0 0 1000

total_filtered_loci 0 0 1000

This block indicates how filtering is impacting your final dataset. Each filter

is applied in order from top to bottom, and the number of loci removed because

of each filter is shown in the applied_order column. The total number of

retained_loci after each filtering step is displayed in the final column.

This is a good place for inspecting how your filtering thresholds are impacting

your final dataset. For example, you might see that most loci are being filterd

by min_sample_locus (a very common result), in which case you might reduce

this threshold in your params file and re-run step 7 in order to retain more loci. You can use branching, so you can re-run part of the analysis, without overwriting the output you already generated.

The next block shows a simple summary of the number of loci retained for each sample in the final dataset. Pretty straightforward. If you have some samples that have very low sample_coverage here it might be good to remove them and re-run step 7. Also this can be done by using branching.

## The number of loci recovered for each Sample.

## ipyrad API location: [assembly].stats_dfs.s7_samples

sample_coverage

1A_0 1000

1B_0 1000

1C_0 1000

1D_0 1000

2E_0 1000

2F_0 1000

2G_0 1000

2H_0 1000

3I_0 1000

3J_0 1000

3K_0 1000

3L_0 1000

The next block is locus_coverage, which indicates the number of loci that

contain exactly a given number of samples, and sum_coverage is just the

running total of these in ascending order. So here, if it weren’t being

filtered, locus coverage in the 1 column would indicate singletons (only

one sample at this locus), and locus coverage in the 10 column indicates

loci with full coverage (all samples have data at these loci).

Note: It’s important to notice that locus coverage below your

min_sample_locusparameter setting will all naturally equal 0, since by definition these are being removed.

## The number of loci for which N taxa have data.

## ipyrad API location: [assembly].stats_dfs.s7_loci

locus_coverage sum_coverage

1 0 0

2 0 0

3 0 0

4 0 0

5 0 0

6 0 0

7 0 0

8 0 0

9 0 0

10 0 0

11 0 0

12 1000 1000

Whereas the previous block indicated samples per locus, below we are looking at

SNPs per locus. In a similar fashion as above, these columns record the counts

of loci containing given numbers of variable sites and parsimony informative

sites (pis). For example, in the 2 row, this indicates the number of loci

with 2 variable sites (174), and the number of loci with 2 pis (48). The sum_*

columns simply indicate the running total in ascending order.

Note: This block can be a little tricky because loci can end up getting double-counted. For example, a locus with 1 pis, and 2 autapomorphies will be counted once in the 3 row for

var, and once in the 1 row forpis. Apply care when interpreting these values.

The distribution of SNPs (var and pis) per locus.

## var = Number of loci with n variable sites (pis + autapomorphies)

## pis = Number of loci with n parsimony informative site (minor allele in >1 sample)

## ipyrad API location: [assembly].stats_dfs.s7_snps

## The "reference" sample is included if present unless 'exclude_reference=True'

var sum_var pis sum_pis

0 1 0 163 0

1 5 5 288 288

2 20 45 264 816

3 46 183 160 1296

4 66 447 70 1576

5 111 1002 36 1756

6 164 1986 13 1834

7 141 2973 5 1869

8 122 3949 1 1877

9 121 5038 0 1877

10 76 5798 0 1877

11 57 6425 0 1877

12 30 6785 0 1877

13 14 6967 0 1877

14 15 7177 0 1877

15 4 7237 0 1877

16 3 7285 0 1877

17 4 7353 0 1877

The next block displays statistics for each sample in the final dataset.

Many of these stats will already be familiar, but this provides a nice compact

view on how each sample is represented in the output. The one new stat here is

loci_in_assembly, which indicates how many loci each sample has data for.

## Final Sample stats summary

state reads_raw reads_passed_filter refseq_mapped_reads refseq_unmapped_reads clusters_total clusters_hidepthhetero_est error_est reads_consens loci_in_assembly

1A_0 7 19835 19835 19835 0 1000 1000 0.001842 0.000773 1000 1000

1B_0 7 20071 20071 20071 0 1000 1000 0.001861 0.000751 1000 1000

1C_0 7 19969 19969 19969 0 1000 1000 0.002045 0.000761 1000 1000

1D_0 7 20082 20082 20082 0 1000 1000 0.001813 0.000725 1000 1000

2E_0 7 20004 20004 20004 0 1000 1000 0.002006 0.000767 1000 1000

2F_0 7 19899 19899 19899 0 1000 1000 0.002045 0.000761 1000 1000

2G_0 7 19928 19928 19928 0 1000 1000 0.001858 0.000765 1000 1000

2H_0 7 20110 20110 20110 0 1000 1000 0.002129 0.000730 1000 1000

3I_0 7 20078 20078 20078 0 1000 1000 0.001961 0.000749 1000 1000

3J_0 7 19965 19965 19965 0 1000 1000 0.001950 0.000748 1000 1000

3K_0 7 19846 19846 19846 0 1000 1000 0.001959 0.000768 1000 1000

3L_0 7 20025 20025 20025 0 1000 1000 0.001956 0.000753 1000 1000

The final block displays some very brief, but informative, summaries of missingness in the assembly at both the sequence and the SNP level:

## Alignment matrix statistics:

sequence matrix size: (12, 148725), 0.00% missing sites.

snps matrix size: (12, 7353), 0.00% missing sites.

For some downstream analyses we might need more than just the default output

formats, so lets rerun step 7 and generate all supported output formats. This

can be accomplished by editing the params-peddrad.txt file and setting the

requested output_formats to * (the wildcard character):

And change his line:

* ## [27] [output_formats]: Output formats (see docs)

After this we must now re-run step 7, but this time including the -f flag,

to force overwriting the output files that were previously generated. More

information about all supported output formats can be found in the ipyrad docs.

$ ipyrad -p params-peddrad.txt -s 7 -c 16 -f

Congratulations! You’ve completed your first RAD-Seq assembly. Now you can try

applying what you’ve learned to assemble your own real data. Please consult the

ipyrad online documentation for details about

many of the more powerful features of ipyrad, including reference sequence

mapping, assembly branching, and the extensive analysis toolkit, which

includes extensive downstream analysis tools for such things as clustering and

population assignment, phylogenetic tree inference, quartet-based species tree

inference, and much more.