ipyrad command line tutorial - Part I

This is the first part of the full tutorial for the command line interface (CLI) for ipyrad. In this tutorial we’ll walk through the entire assembly and analysis process. This is meant as a broad introduction to familiarize users with the general workflow, and some of the parameters and terminology. We will use as an example in this tutorial the Anolis data set from the first part of class. However, you can follow along with one of the other example data sets if you like and although your results will vary the procedure will be identical.

If you are new to RADseq analyses, this tutorial will provide a simple overview of how to execute ipyrad, what the data files look like, how to check that your analysis is working, and what the final output formats will be. We will also cover how to run ipyrad on a cluster and to do so efficiently.

Each grey cell in this tutorial indicates a command line interaction.

Lines starting with $ indicate a command that should be executed

in a terminal connected to the Habanero cluster, for example by copying and

pasting the text into your terminal. Elements in code cells surrounded

by angle brackets (e.g.

## Example Code Cell.

## Create an empty file in my home directory called `watdo.txt`

$ touch ~/watdo.txt

## Print "wat" to the screen

$ echo "wat"

wat

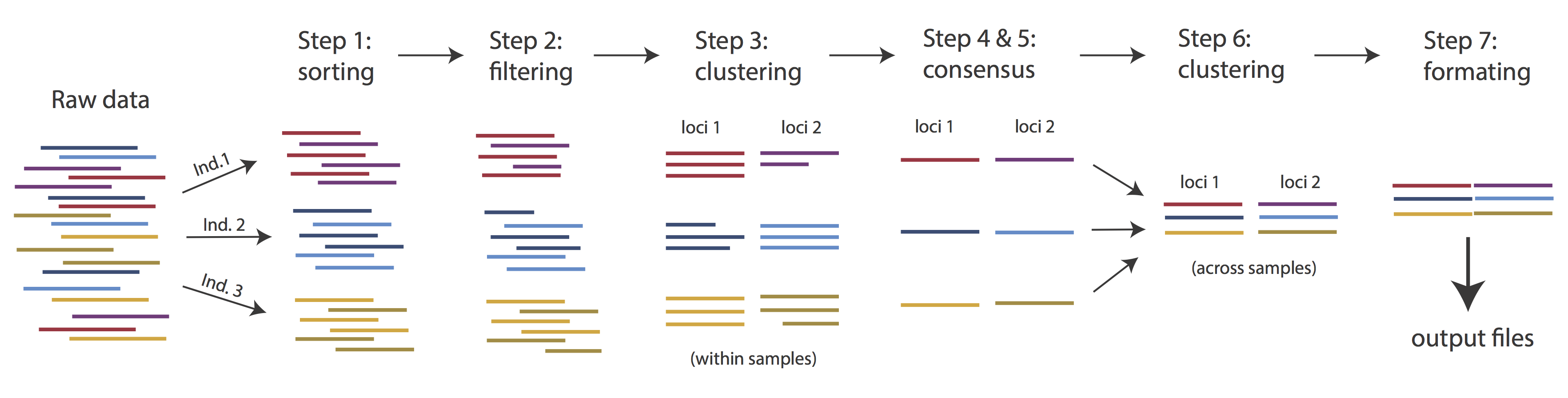

Overview of Assembly Steps

Very roughly speaking, ipyrad exists to transform raw data coming off the sequencing instrument into output files that you can use for downstream analysis.

The basic steps of this process are as follows:

- Step 1 - Demultiplex/Load Raw Data

- Step 2 - Trim and Quality Control

- Step 3 - Cluster or reference-map within Samples

- Step 4 - Calculate Error Rate and Heterozygosity

- Step 5 - Call consensus sequences/alleles

- Step 6 - Cluster across Samples

- Step 7 - Apply filters and write output formats

Note on files in the project directory: Assembling RAD-seq type sequence data requires a lot of different steps, and these steps generate a lot of intermediary files. ipyrad organizes these files into directories, and it prepends the name of your assembly to each directory with data that belongs to it. One result of this is that you can have multiple assemblies of the same raw data with different parameter settings and you don’t have to manage all the files yourself! (See Branching assemblies for more info). Another result is that you should not rename or move any of the directories inside your project directory, unless you know what you’re doing or you don’t mind if your assembly breaks.

Getting started

The magic of the Jupyter Hub we’re using for this workshop conceals some of the complexity of working in a real production environment, such as with an HPC system at your home campus. In this case we provide extensive documentation about using ipyrad on HPC systems elsewhere on the RADCamp site.

ipyrad help

To better understand how to use ipyrad, let’s take a look at the help argument. We will use some of the ipyrad arguments in this tutorial (for example: -n, -p, -s, -c, -r). The complete list of optional arguments and their explanation can be accessed with the --help flag:

$ ipyrad --help

usage: ipyrad [-h] [-v] [-r] [-f] [-q] [-d] [-n new] [-p params]

[-b [branch [branch ...]]] [-m [merge [merge ...]]] [-s steps]

[-c cores] [-t threading] [--MPI] [--preview]

[--ipcluster [ipcluster]] [--download [download [download ...]]]

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

-v, --version show program's version number and exit

-r, --results show results summary for Assembly in params.txt and

exit

-f, --force force overwrite of existing data

-q, --quiet do not print to stderror or stdout.

-d, --debug print lots more info to ipyrad_log.txt.

-n new create new file 'params-{new}.txt' in current

directory

-p params path to params file for Assembly:

params-{assembly_name}.txt

-b [branch [branch ...]]

create a new branch of the Assembly as

params-{branch}.txt

-m [merge [merge ...]]

merge all assemblies provided into a new assembly

-s steps Set of assembly steps to perform, e.g., -s 123

(Default=None)

-c cores number of CPU cores to use (Default=0=All)

-t threading tune threading of binaries (Default=2)

--MPI connect to parallel CPUs across multiple nodes

--preview run ipyrad in preview mode. Subset the input file so

it'll runquickly so you can verify everything is

working

--ipcluster [ipcluster]

connect to ipcluster profile (default: 'default')

--download [download [download ...]]

download fastq files by accession (e.g., SRP or SRR)

* Example command-line usage:

ipyrad -n data ## create new file called params-data.txt

ipyrad -p params-data.txt ## run ipyrad with settings in params file

ipyrad -p params-data.txt -s 123 ## run only steps 1-3 of assembly.

ipyrad -p params-data.txt -s 3 -f ## run step 3, overwrite existing data.

* HPC parallelization across 32 cores

ipyrad -p params-data.txt -s 3 -c 32 --MPI

* Print results summary

ipyrad -p params-data.txt -r

* Branch/Merging Assemblies

ipyrad -p params-data.txt -b newdata

ipyrad -m newdata params-1.txt params-2.txt [params-3.txt, ...]

* Subsample taxa during branching

ipyrad -p params-data.txt -b newdata taxaKeepList.txt

* Download sequence data from SRA into directory 'sra-fastqs/'

ipyrad --download SRP021469 sra-fastqs/

* Documentation: http://ipyrad.readthedocs.io

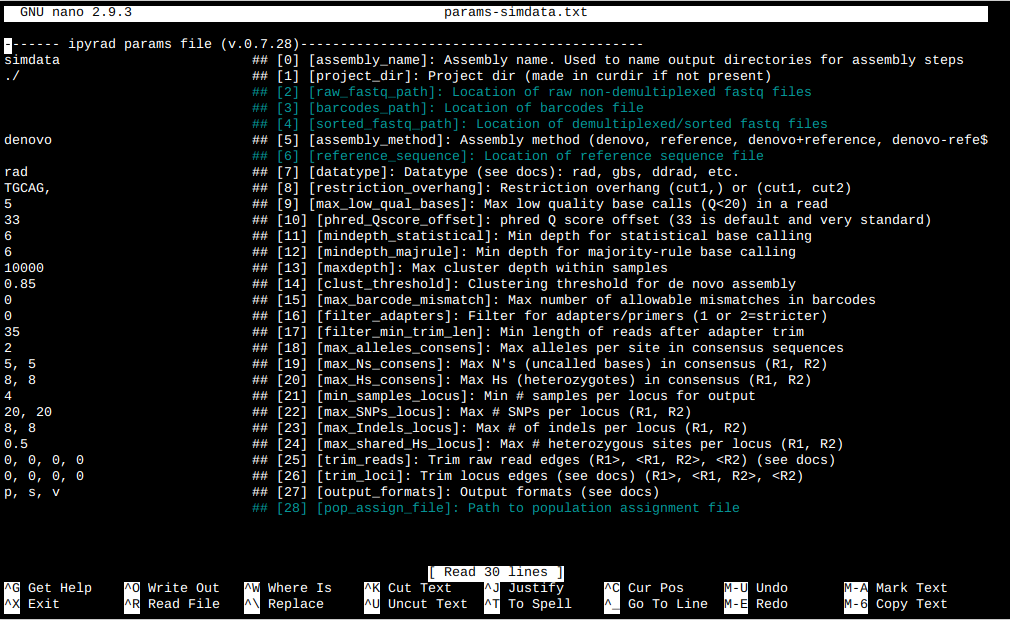

Create a new parameters file

ipyrad uses a text file to hold all the parameters for a given assembly.

Start by creating a new parameters file with the -n flag. This flag

requires you to pass in a name for your assembly. In the example we use

simdata but the name can be anything at all. Once you start

analysing your own data you might call your parameters file something

more informative, like the name of your organism and some details on the settings.

# go to our working directory

$ cd ~/work

# create a new params file named 'simdata'

$ ipyrad -n simdata

This will create a file in the current directory called params-simdata.txt. The

params file lists on each line one parameter followed by a ## mark, then the name of the

parameter, and then a short description of its purpose. Lets take a look at it.

$ cat params-simdata.txt

------- ipyrad params file (v.0.7.28)-------------------------------------------

simdata ## [0] [assembly_name]: Assembly name. Used to name output directories for assembly steps

./ ## [1] [project_dir]: Project dir (made in curdir if not present)

## [2] [raw_fastq_path]: Location of raw non-demultiplexed fastq files

## [3] [barcodes_path]: Location of barcodes file

## [4] [sorted_fastq_path]: Location of demultiplexed/sorted fastq files

denovo ## [5] [assembly_method]: Assembly method (denovo, reference, denovo+reference, denovo-reference)

## [6] [reference_sequence]: Location of reference sequence file

rad ## [7] [datatype]: Datatype (see docs): rad, gbs, ddrad, etc.

TGCAG, ## [8] [restriction_overhang]: Restriction overhang (cut1,) or (cut1, cut2)

5 ## [9] [max_low_qual_bases]: Max low quality base calls (Q<20) in a read

33 ## [10] [phred_Qscore_offset]: phred Q score offset (33 is default and very standard)

6 ## [11] [mindepth_statistical]: Min depth for statistical base calling

6 ## [12] [mindepth_majrule]: Min depth for majority-rule base calling

10000 ## [13] [maxdepth]: Max cluster depth within samples

0.85 ## [14] [clust_threshold]: Clustering threshold for de novo assembly

0 ## [15] [max_barcode_mismatch]: Max number of allowable mismatches in barcodes

0 ## [16] [filter_adapters]: Filter for adapters/primers (1 or 2=stricter)

35 ## [17] [filter_min_trim_len]: Min length of reads after adapter trim

2 ## [18] [max_alleles_consens]: Max alleles per site in consensus sequences

5, 5 ## [19] [max_Ns_consens]: Max N's (uncalled bases) in consensus (R1, R2)

8, 8 ## [20] [max_Hs_consens]: Max Hs (heterozygotes) in consensus (R1, R2)

4 ## [21] [min_samples_locus]: Min # samples per locus for output

20, 20 ## [22] [max_SNPs_locus]: Max # SNPs per locus (R1, R2)

8, 8 ## [23] [max_Indels_locus]: Max # of indels per locus (R1, R2)

0.5 ## [24] [max_shared_Hs_locus]: Max # heterozygous sites per locus (R1, R2)

0, 0, 0, 0 ## [25] [trim_reads]: Trim raw read edges (R1>, <R1, R2>, <R2) (see docs)

0, 0, 0, 0 ## [26] [trim_loci]: Trim locus edges (see docs) (R1>, <R1, R2>, <R2)

p, s, v ## [27] [output_formats]: Output formats (see docs)

## [28] [pop_assign_file]: Path to population assignment file

In general the defaults are sensible, and we won’t mess with them for now, but there are a few parameters we must change: the path to the raw data, the dataype, the restriction overhang sequence, and the barcodes file.

We will use the nano text editor to modify params-simdata.txt and change

these parameters:

$ nano params-simdata.txt

Nano is a command line editor, so you’ll need to use only the arrow keys on the keyboard for navigating around the file. Nano accepts a few special keyboard commands for doing things other than modifying text, and it lists these on the bottom of the frame.

We need to specify where the raw data files are located, the type of data we are using (.e.g., ‘gbs’, ‘rad’, ‘ddrad’, ‘pairddrad), and which enzyme cut site overhangs are expected to be present on the reads. Below are the parameter setings you’ll need to change for the simulated single-end RAD example data:

/home/jovyan/ro-data/ipsimdata/rad_example_R1_.fastq.gz ## [2] [raw_fastq_path]: Location ofraw non-demultiplexed fastq files

/home/jovyan/ro-data/ipsimdata/rad_example_barcodes.txt ## [3] [barcodes_path]: Location of barcodes file

rad ## [7] [datatype]: Datatype (see docs): rad, gbs, ddrad, etc.

TGCAG, ## [8] [restriction_overhang]: Restriction overhang (cut1,) or (cut1, cut2)

After you change these parameters you may save and exit nano by typing CTRL+o (to write Output), and then CTRL+x (to eXit the program).

Note: The

CTRL+xnotation indicates that you should hold down the control key (which is often styled ‘ctrl’ on the keyboard) and then push ‘x’.

Once we start running the analysis ipyrad will create several new

directories to hold the output of each step for this assembly. By

default the new directories are created in the project_dir

directory and use the prefix specified by the assembly_name parameter.

Because we use the default (./) for the project_dir for this tutorial, all these

intermediate directories will be of the form: ~/work/simdata_*,

or the analagous name that you used for your assembly name.

Note: Again, the

./notation indicates the current working directory. You can always view the current working directory with thepwdcommand (print working directory).

Input data format

Before we get started let’s take a look at what the raw data looks like.

Your input data will be in fastQ format, usually ending in .fq,

.fastq, .fq.gz, or .fastq.gz. The file/s may be compressed with

gzip so that they have a .gz ending, but they do not need to be. Lets take

a look at first three reads of one of the simulated data.

$ zcat /home/jovyan/ro-data/ipsimdata/rad_example_R1_.fastq.gz | head -n 12

@lane1_locus0_2G_0_0 1:N:0:

CTCCAATCCTGCAGTTTAACTGTTCAAGTTGGCAAGATCAAGTCGTCCCTAGCCCCCGCGTCCGTTTTTACCTGGTCGCGGTCCCGACCCAGCTGCCCCC

+

BBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBB

@lane1_locus0_2G_0_1 1:N:0:

CTCCAATCCTGCAGTTTAACTGTTCAAGTTGGCAAGATCAAGTCGTCCCTAGCCCCCGCGTCCGTTTTTACCTGGTCGCGGTCCCCACCCAGCTGCCCCC

+

BBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBB

@lane1_locus0_2G_0_2 1:N:0:

CTCCAATCCTGCAGTTTAACTGTTCAAGTTGGCAAGATCAAGTCGTCCCTAGCCCCCGCGTCCGTTTTTACCTGGTCGCGGTCCCGACCCAGCTGCCCCC

+

BBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBB

Exercise for the reader: Can you find and verify the overhang sequence in the simulated data? Hint: It’s not right at the beginning of the sequence, which is where you might expect it to be…. It’s always a good idea to look at your data to check for the cut site. Your first sign of a messy dataset is lots of off target reads, basically stuff that got sequenced that isn’t associated with a restriction enzyme cutsite.

Each read is composed of four lines. The first is the name of the read (its location on the plate). The second line contains the sequence data. The third line is unused. And the fourth line is the quality scores for the base calls. The FASTQ wikipedia page has a good figure depicting the logic behind how quality scores are encoded. Here you can see that the simulated data are generated with uniformly high quality scores. Quality scores in real data are much more all over the place:

@D00656:123:C6P86ANXX:8:2201:3857:34366 1:Y:0:8

TGCATGTTTATTGTCTATGTAAAAGGAAAAGCCATGCTATCAGAGATTGGCCTGGGGGGGGGGGGCAAATACATGAAAAAGGGAAAGGCAAAATG

+

;=11>111>1;EDGB1;=DG1=>1:EGG1>:>11?CE1<>1<1<E1>ED1111:00CC..86DG>....//8CDD/8C/....68..6.:8....

Step 1: Demultiplexing the raw data

Commonly, sequencing facilities will give you one giant .gz file that contains all the reads from all the samples all mixed up together. Step 1 is all about sorting out which reads belong to which samples, so this is where the barcodes file comes in handy. The barcodes file is a simple text file mapping sample names to barcode sequences. Lets look at the simulated barcodes:

$ cat /home/jovyan/ro-data/ipsimdata/rad_example_barcodes.txt

1A_0 CATCATCAT

1B_0 CCAGTGATA

1C_0 TGGCCTAGT

1D_0 GGGAAAAAC

2E_0 GTGGATATC

2F_0 AGAGCCGAG

2G_0 CTCCAATCC

2H_0 CTCACTGCA

3I_0 GGCGCATAC

3J_0 CCTTATGTC

3K_0 ACGTGTGTG

3L_0 TTACTAACA

Here the barcodes are all the same length, but ipyrad can also handle variable length barcodes, and in some cases multiplexed barcodes (3RAD and variants). We can also allow for varying amounts of sequencing error in the barcode in the barcode sequences (parameter 15, max_barcode_mismatch).

Note on step 1: Occasionally sequencing facilities will send back data already demultiplexed to samples. This is totally fine, and is handled natively by ipyrad. In this case you would use the

sorted_fastq_pathin the params file to indiciate the sample fastq.gz files. ipyrad will then scan the samples and load in the raw data.

Now lets run step 1! For the simulated data this will take <10 seconds.

Special Note: In command line mode please be aware to always specify the number of cores with the

-cflag. If you do not specify the number of cores ipyrad assumes you want all of them, which will result in you hogging up all the CPU. We only have 40 cores so everybody has to share!

## -p the params file we wish to use

## -s the step to run

## -c the number of cores to allocate <-- Important!

$ ipyrad -p params-simdata.txt -s 1 -c 4

-------------------------------------------------------------

ipyrad [v.0.7.28]

Interactive assembly and analysis of RAD-seq data

-------------------------------------------------------------

New Assembly: simdata

establishing parallel connection:

host compute node: [4 cores] on e305ff77a529

Step 1: Loading sorted fastq data to Samples

Step 1: Demultiplexing fastq data to Samples

[####################] 100% sorting reads | 0:00:04

[####################] 100% writing/compressing | 0:00:01

In-depth operations of running an ipyrad step

Any time ipyrad is invoked it performs a few housekeeping operations:

- Load the assembly object - Since this is our first time running any steps we need to initialize our assembly.

- Start the parallel cluster - ipyrad uses a parallelization library called

ipyparallel. Every time we start a step we fire up the parallel clients. This makes your assemblies go smokin’ fast. - Do the work - Actually perform the work of the requested step(s) (in this case demux’ing in sample reads).

- Save, clean up, and exit - Save the state of the assembly and spin down the ipyparallel cluster.

As a convenience ipyrad internally tracks the state of all your steps in your

current assembly, so at any time you can ask for results by invoking the -r flag.

We also use the -p flag to tell it which params file (i.e., which assembly) we

want to print stats for.

## -r fetches informative results from currently executed steps

$ ipyrad -p params-simdata.txt -r

Summary stats of Assembly simdata

------------------------------------------------

state reads_raw

1A_0 1 19862

1B_0 1 20043

1C_0 1 20136

1D_0 1 19966

2E_0 1 20017

2F_0 1 19933

2G_0 1 20030

2H_0 1 20199

3I_0 1 19885

3J_0 1 19822

3K_0 1 19965

3L_0 1 20008

Full stats files

------------------------------------------------

step 1: ./simdata_fastqs/s1_demultiplex_stats.txt

step 2: None

step 3: None

step 4: None

step 5: None

step 6: None

step 7: None

If you want to get even more info ipyrad tracks all kinds of wacky stats and saves them to files inside the directories it creates for each step. For instance to see full stats for step 1 (the wackyness of the step 1 stats at this point isn’t very interesting, but we’ll see stats for later steps are more verbose):

$ cat simdata_fastqs/s1_demultiplex_stats.txt

raw_file total_reads cut_found bar_matched

rad_example_R1_.fastq 239866 239866 239866

sample_name total_reads

1A_0 19862

1B_0 20043

1C_0 20136

1D_0 19966

2E_0 20017

2F_0 19933

2G_0 20030

2H_0 20199

3I_0 19885

3J_0 19822

3K_0 19965

3L_0 20008

sample_name true_bar obs_bar N_records

1A_0 CATCATCAT CATCATCAT 19862

1B_0 CCAGTGATA CCAGTGATA 20043

1C_0 TGGCCTAGT TGGCCTAGT 20136

1D_0 GGGAAAAAC GGGAAAAAC 19966

2E_0 GTGGATATC GTGGATATC 20017

2F_0 AGAGCCGAG AGAGCCGAG 19933

2G_0 CTCCAATCC CTCCAATCC 20030

2H_0 CTCACTGCA CTCACTGCA 20199

3I_0 GGCGCATAC GGCGCATAC 19885

3J_0 CCTTATGTC CCTTATGTC 19822

3K_0 ACGTGTGTG ACGTGTGTG 19965

3L_0 TTACTAACA TTACTAACA 20008

no_match _ _ 0

Another early indicator of trouble is if you have a ton of reads that are no_match.

This means maybe your barcodes file is wrong, or maybe your library prep went poorly. Here,

with the simulated data we have no unmatched barcodes, because, well, it’s simulated.

Step 2: Filter reads

This step filters reads based on quality scores and maximum number of uncalled bases, and can be used to detect Illumina adapters in your reads, which is sometimes a problem under a couple different library prep scenarios. Since it’s not atypical to have adapter contamination issues and to have a little noise toward the distal end of the reads lets imagine this is true of the simulated data, and we’ll try to account for this by trimming reads to 90bp and using aggressive adapter filtering.

Edit your params file again with nano:

nano params-simdata.txt

and change the following two parameter settings:

2 ## [16] [filter_adapters]: Filter for adapters/primers (1 or 2=stricter)

0, 90, 0, 0 ## [25] [trim_reads]: Trim raw read edges (R1>, <R1, R2>, <R2) (see docs)

Note: Saving and quitting from

nano:CTRL+othenCTRL+x

$ ipyrad -p params-simdata.txt -s 2 -c 4

-------------------------------------------------------------

ipyrad [v.0.7.28]

Interactive assembly and analysis of RAD-seq data

-------------------------------------------------------------

loading Assembly: simdata

from saved path: ~/work/simdata.json

establishing parallel connection:

host compute node: [4 cores] on darwin

Step 2: Filtering reads

[####################] 100% processing reads | 0:00:12

The filtered files are written to a new directory called simdata_edits. Again,

you can look at the results output by this step and also some handy stats tracked

for this assembly.

## View the output of step 2

$ cat simdata_edits/s2_rawedit_stats.txt

reads_raw trim_adapter_bp_read1 trim_quality_bp_read1 reads_filtered_by_Ns reads_filtered_by_minlen reads_passed_filter

1A_0 19862 360 0 0 0 19862

1B_0 20043 362 0 0 0 20043

1C_0 20136 349 0 0 0 20136

1D_0 19966 404 0 0 0 19966

2E_0 20017 394 0 0 0 20017

2F_0 19933 376 0 0 0 19933

2G_0 20030 381 0 0 0 20030

2H_0 20199 386 0 0 1 20198

3I_0 19885 372 0 0 0 19885

3J_0 19822 381 0 0 0 19822

3K_0 19965 382 0 0 0 19965

3L_0 20008 424 0 0 0 20008

It’s a little boring, the reads are too clean. Here is an example of something

like you’d see from real data (this is the Anolis dataset). Notice the reads_passed_filter

value. This dataset is decent, as you can see we’re losing < 10% of the reads per sample,

mostly due to the minimum length cutoff.

reads_raw trim_adapter_bp_read1 trim_quality_bp_read1 reads_filtered_by_Ns reads_filtered_by_minlen reads_passed_filter

punc_IBSPCRIB0361 250000 108761 160210 66 12415 237519

punc_ICST764 250000 107320 178463 68 13117 236815

punc_JFT773 250000 110684 190803 46 9852 240102

punc_MTR05978 250000 102932 144773 54 12242 237704

punc_MTR17744 250000 103394 211363 55 9549 240396

punc_MTR21545 250000 119191 161709 63 21972 227965

punc_MTR34414 250000 109207 193401 54 16372 233574

punc_MTRX1468 250000 119746 134069 45 19052 230903

punc_MTRX1478 250000 116009 184189 53 16549 233398

punc_MUFAL9635 250000 114492 182877 61 18071 231868

## Get current stats including # raw reads and # reads after filtering.

$ ipyrad -p params-simdata.txt -r

You might also take a closer look at the filtered reads:

$ zcat simdata_edits/1A_0.trimmed_R1_.fastq.gz | head -n 12

@lane1_locus0_1A_0_0 1:N:0:

TGCAGTTTAACTGTTCAAGTTGGCAAGATCAAGTCGTCCCTAGCCCCCGCGTCCGTTTTTACCTGGTCGCGGTCCCGACCCAGCTGCCCC

+

BBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBB

@lane1_locus0_1A_0_1 1:N:0:

TGCAGTTTAACTGTTCAAGTTGGCAAGATCAAGTCGTCCCTAGCCCCCGCGTCCGTTTTTACCTGGTCGCGGTCCCGACCCAGCTGCCCC

+

BBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBB

@lane1_locus0_1A_0_2 1:N:0:

TGCAGTTTAACTGTTCAAGTTGGCAAGATCAAGTCGTCCCTAGCCCCCGCGTCCGTTTTTACCTGGTCGCGGTCCCGACCCAGCTGCCCC

+

BBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBB

Since the adapter content of the simulated data is effectively 0, the net effect of step 2 is that the reads have been trimmed to 90bp. This isn’t necessary here, but it provides a good example since real data typically will need trimming.

Step 3: clustering within-samples

Step 3 de-replicates and then clusters reads within each sample by the

set clustering threshold and then writes the clusters to new files in a

directory called simdata_clust_0.85. Intuitively we are trying to

identify all the reads that map to the same locus within each sample.

The clustering threshold specifies the minimum percentage of sequence

similarity below which we will consider two reads to have come from

different loci.

The true name of this output directory will be dictated by the value you

set for the clust_threshold parameter in the params file. This makes it

very easy to test different clustering thresholds, and keep the different

runs organized (since you will have for example simdata_clust_0.85 and

simdata_clust_0.9).

You can see the default value is 0.85, so our default directory is named accordingly. This value dictates the percentage of sequence similarity that reads must have in order to be considered reads at the same locus. You’ll more than likely want to experiment with this value, but 0.85 is a reliable default, balancing over-splitting of loci vs over-lumping. Don’t mess with this until you feel comfortable with the overall workflow, and also until you’ve learned about Branching assemblies (which we will get to later this afternoon).

There have been many papers written comparing how results of assemblies vary depending on the clustering threshold. In general, my advice is to use a value between about .82 and .95. Within this region results typically do not vary too significantly, whereas above .95 you will oversplit loci and recover fewer SNPs.

It’s also possible to incorporate information from a reference genome to improve clustering at this step, if such a resources is available for your organism (or one that is relatively closely related). We will not cover reference based assemblies in this workshop, but you can refer to the ipyrad documentation for more information.

Note on performance: Steps 3 and 6 generally take considerably longer than any of the other steps, due to the resource intensive clustering and alignment phases. These can take on the order of 10-100x as long as the next longest running step. This depends heavily on the number of samples in your dataset, the number of cores on your computer, the length(s) of your reads, and the “messiness” of your data in terms of the number of unique loci present (this can vary from a few thousand to many millions).

Now lets run step 3:

$ ipyrad -p params-simdata.txt -s 3 -c 4

-------------------------------------------------------------

ipyrad [v.0.7.28]

Interactive assembly and analysis of RAD-seq data

-------------------------------------------------------------

loading Assembly: simdata

from saved path: ~/work/simdata.json

establishing parallel connection:

host compute node: [4 cores] on e305ff77a529

Step 3: Clustering/Mapping reads within samples

[####################] 100% 0:00:01 | concatenating

[####################] 100% 0:00:01 | dereplicating

[####################] 100% 0:00:00 | clustering/mapping

[####################] 100% 0:00:00 | building clusters

[####################] 100% 0:00:00 | chunking clusters

[####################] 100% 0:00:03 | aligning clusters

[####################] 100% 0:00:00 | concat clusters

[####################] 100% 0:00:00 | calc cluster stats

In-depth operations of step 3:

- concatenating - Concatenate files from merged assemblies

- dereplicating - Merge all identical reads

- clustering - Find reads matching by sequence similarity threshold

- building clusters - Group similar reads into clusters

- chunking - Subsample cluster files to improve performance of alignment step

- aligning - Align all clusters

- concatenating - Gather chunked clusters into one full file of aligned clusters

- calc cluster stats - Just as it says!

Again we can examine the results. The stats output tells you how many clusters were found (‘clusters_total’), and the number of clusters that pass the mindepth thresholds (‘clusters_hidepth’). We go into more detail about mindepth settings in some of the advanced tutorials but for now all you need to know is that by default step 3 will filter out clusters that only have a handful of reads on the assumption that it will be difficult to accurately call bases at such low depth.

$ ipyrad -p params-simdata.txt -r

Summary stats of Assembly simdata

------------------------------------------------

state reads_raw reads_passed_filter clusters_total clusters_hidepth

1A_0 3 19862 19862 1000 1000

1B_0 3 20043 20043 1000 1000

1C_0 3 20136 20136 1000 1000

1D_0 3 19966 19966 1000 1000

2E_0 3 20017 20017 1000 1000

2F_0 3 19933 19933 1000 1000

2G_0 3 20030 20030 1000 1000

2H_0 3 20199 20198 1000 1000

3I_0 3 19885 19885 1000 1000

3J_0 3 19822 19822 1000 1000

3K_0 3 19965 19965 1000 1000

3L_0 3 20008 20008 1000 1000

Full stats files

------------------------------------------------

step 1: ./simdata_fastqs/s1_demultiplex_stats.txt

step 2: ./simdata_edits/s2_rawedit_stats.txt

step 3: ./simdata_clust_0.85/s3_cluster_stats.txt

Again, the final output of step 3 is dereplicated, clustered files for

each sample in ./simdata_0.85/. You can get a feel for what

this looks like by examining a portion of one of the files.

## Same as above, `zcat` unzips and prints to the screen and

## `head -n 24` means just show me the first 24 lines.

$ zcat simdata_clust_0.85/1A_0.clustS.gz | head -n 24

009149cc23d2367f21b67ac0060d9f2f;size=18;*

TGCAGATAAATCAAACTGCAGCTTGATATGGGCTTCGACCCAGTGGTGGTAGCCTCTCTCTCCCAGTATAACCTCGACCCCAAAATCGCA

d498af3d4575b871de6d5a7f239279ea;size=1;+

TGCAGATAAATCAAACTGCAGCTTGATATGGGCTTCGACCCAGTGGTGGTAGCCTCTCTCTCCCAGTATAACCTCGACCCCAAAATCGCT

b71555537ed7f88329fda094cc6cef8a;size=1;+

TGCAGATAAATCAAACTGCAGCTTGATATGGGCTTCGACCCAGTGGTGGTAGCGTCTCTCTCCCAGTATAACCTCGACCCCAAAATCGCA

//

//

00f1daaa8dd241bd72db91aa62b31bb4;size=8;*

TGCAGGGGTTAGGCGTATCTGCCAAAGATTCTTCGATCGTGATGATTCTAGACGACAATACACCTGATGCTTCTCGCATGCATAGCAATG

6780649efadfc8c182cfd2af7071316b;size=8;+

TGCAGGGGTTAGGCGTATCTGCCAAAGATTCTTCGATCGTGATGATTCTAGAGGACAATACACCTGATGCTTCTCGCATGCATAGCAATG

23a7b43b7f5008017574400c460982dc;size=1;+

TGCAGGGGTTAGGCGTATCTTCCAAAGATTCTTCGATCGTGATGATTCTAGACGACAATACACCTGATGCTTCTCGCATGCATAGCAATG

e6830f9099df558397f0fd28bf9568b6;size=1;+

TGCAGGGGTTAGGCGTATCTGCCAAAGATTCTTCGATCGTGATGATTCTAGACGATAATACACCTGATGCTTCTCGCATGCATAGCAATG

//

//

013b4e939c785d94369ea933f7f98f0c;size=18;*

TGCAGATACTTCGCCCGGTTCTCCATACCCCATTCTTTGCTGCTTCTTCTGAGCGCACTCGACCTATGCCTAGTCGCACCTCGCATATTT

a7e612c565f1d70f054864759b58205f;size=1;+

TGCAGATACTTCGCCCGGTTCTCCATACCCCATTCTTTGCTGCTTCTTCTGAGCGCACTCGACCTATGCCTAGTCCCACCTCGCATATTT

//

//

Reads that are sufficiently similar (based on the above sequence similarity threshold) are grouped together in clusters separated by “//”. For the second cluster above this is probably heterozygous with some sequencing error, and the first and third clusters are probably homozygous. Again, the simulated data is too clean to get a real picture of how tricky real data can be. Looking again at the Anolis data:

000e3bb624e3bd7e91b47238b7314dc6;size=4;*

TGCATATCACAAGAGAAGAAAGCCACTAATTAAGGGGAAAAGAAAAGCCTCTGATATAGCTCCGATATATCATGC-

75e462e101383cca3db0c02fca80b37a;size=2;-

-GCATATCACAAGAGAAGAAAGCCACTAATTAAGGGGAAAAGAAAAGCCTCTGATATAGCTCCGATATATCATGCA

//

//

001236a2310c39a3a16d96c4c6c48df1;size=4;*

TGCATCTCTTTGGGCTGTTGCTTGGTGGCACACCATGCTGCTTTCTCCTCACTTTTTCTCTCTTTTCCTGAGACT------------------------------

4644056dca0546a270ba897b018624b4;size=2;-

------------------------------CACCATGCTGCTTTCTCCTCACTTTTTCTCTCTTTTCCTGAGACTGAGCCAGGGACAGCGGCTGAGGAGGATGCA

5412b772ec0429af178caf6040d2af30;size=1;+

TGCATTTCTTTGGGCTGTTGCTTGGTGGCACACCATGCTGCTTTCTCCTCACTTTTTCTCTCTTTTCCTGAGACT------------------------------

//

//

Are there truly two alleles (heterozygote) for each of these loci? Are they homozygous with lots of sequencing errors, or a heterozygote with few reads for one of the alleles?

Thankfully, untangling this mess is what step 4 is all about.